The Keeper: In a Parable of Forgiveness, a Rabbi Helps a Nazi Soldier Overcome His Past

Reviewed by Sue Weston and Susan Rosenbluth, Two Sues on the Aisle

Fact can be more unbelievable than fiction. In German director Marcus H. Rosenmüller’s award-winning film, The Keeper, a German-Nazi prisoner of war in a British war camp worms his way into the heart of not only a beautiful young English woman but also her family and indeed the entire soccer-loving community of Manchester and the surrounding area. Amazingly, it’s by and large a true story.

A romantic adaptation of a real-life story about the German goalkeeper, Bert Trautmann, The Keeper, an Anglo-German production, boasts an amazingly effective and affective cast to bring to life a story of love and forgiveness, not only of one person for another, including enemies set on killing each other during time of war, but also of oneself for crimes of commission and omission.

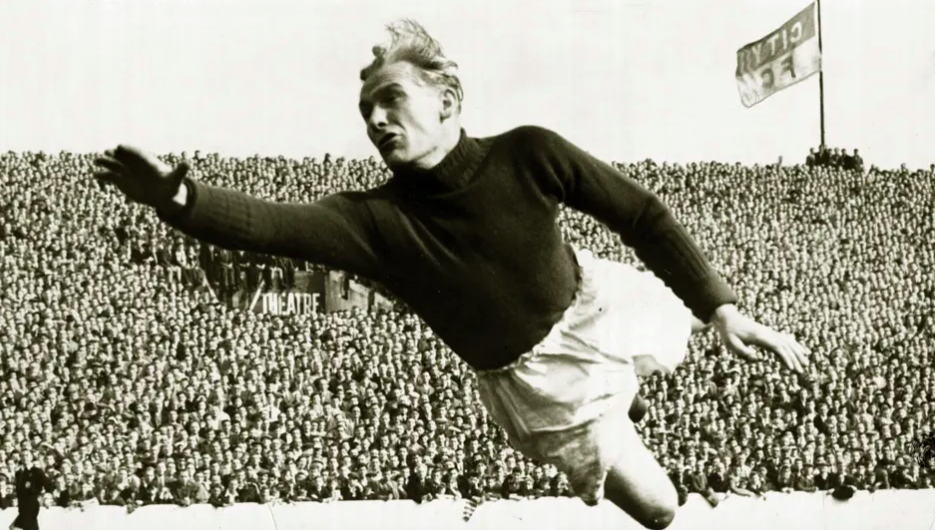

The real Trautmann, played in the film version by David Kross, became famous in the UK for playing despite a broken neck until the final whistle in the 1956 FA Cup for the Manchester City final, a sequence that Rosenmüller turns into an edge-of-your seat thriller, even for those who are not sports fans.

The Nicest German

Rosenmüller and his co-writers, Robert Marciniak and Nicholas Schofield, wisely begin their story in 1944 in the forests near Kiev, where a German unit, including paratrooper Trautmann, is captured and sent to a British POW camp in Lancashire, about 30 miles from Manchester. While the British commander, played by Harry Melling, is filled with righteous indignation and rage at his prisoners, he nevertheless assures them he will abide by all the Geneva Convention protections, which is a far cry from the empty-but-brutal threats that come from a fellow Nazi prisoner.

In this setting, the prisoners, who are forced to work in the camp and for civilians in the neighboring community of St Helens, find respite in casual games of soccer. Yearning for a cigarette, Trautmann dares his fellow inmates to kick a ball that can make it past him into the goal or to give him their supply. His remarkable performance as a goalie makes an impression on Jack Friar (John Henshaw), an amiable local grocer, who sells supplies to the POW camp, and also serves as manager of the forever-losing St Helens Town Soccer League.

Friar manages to arrange for Trautmann to work for him at the grocery and, while he’s at it, play for the team. Driven by his desire to win, Friar must overcome the visceral detestation for any German, and especially a former Wehrmacht soldier, on the part of his own family, especially his lovely daughter, Margaret (the very beautiful Freya Mayor who is able to take the character from a lighthearted young girl to a poignant wife and mother), his neighbors, and his team.

Bert wins them all over, save by save, dive by dive, as he brilliantly guards the goal and accomplishes the seemingly impossible: He brings victory after victory to his team. Dedicated, caring, and respectful, he is by no means the image of a Nazi killer, especially one who has earned an Iron Cross. In short, he’s the nicest German they ever met.

According to historical accounts, the real Trautmann, born Bernhard (he adopted “Bert” in the UK) and known on the British soccer field as “Traut the Kraut,” was somewhat different, and a true appreciation of the film may depend on how little the audience knows about him. While Kross plays Trautmann with almost heroic self-abnegation as a lean, attractive, patient man who can tell his innocent British love that fighting for his country was not a choice and that he would much rather have been dancing with her than making war on the battlefield, the real Trautmann was an enthusiastic member of Hitler Youth from the age of ten and an eager Nazi who volunteered for service, was twice promoted, and witnessed a massacre in a forest by a Nazi assassination squad.

It will never be known if the real Trautmann, like his film counterpart, actually was haunted by memories of a boy (Jewish, Gypsy, or Eastern European) with a soccer ball whose life he could have—but didn’t—save from a fellow Nazi soldier’s bullet. In the film, Bert’s memory shows he wished he had.

In the film, which feels like a true Cinderella story, when the war comes to an end and the POW camp closes, the prisoners are allowed to be repatriated home. Friar worries that his team’s secret weapon will leave. But, true to his word, Bert stays to finish the season. His team wins the finals, and he is invited to take his place as the Manchester City team’s goalie. With the entire Friar family’s blessings, he also marries Margaret.

A Rabbi’s Forgiveness

But Manchester is not St Helens, and the big city’s soccer fans respond with even more loathing than Trautmann experienced at the beginning of his stay in the UK. The city’s sizable Jewish community weighs in heavily, telling the team’s management that if they sign a German goalkeeper, a boycott of the team will be organized.

Trautmann’s professional life, in the film and real life, was saved by an open letter written by Rabbi Alexander Altmann (Butz Ulrich Buse), a German national whose parents were murdered in the Holocaust and who, from 1938 to 1959, served as a Jewish communal spiritual leader in Manchester.

For reasons of his own, Rabbi Altmann published his letter in which he stressed that it is unfair to hold one person responsible for the war crimes committed by the Nazis. In the face of tens of thousands of British citizens marching in mass demonstrations outside the Manchester City Stadium, both Manchester and opposition crowds chanting against Trautmann, and threatening letters addressed to the “Nazi,” Rabbi Altmann wrote: “Each member of the Jewish community is entitled to his own opinion, but despite the terrible cruelties we suffered at the hands of the Germans, we should not try to punish an individual German who is unconnected with these crimes of hatred. If this footballer is a decent fellow, I would say there is no harm in it. Each should be judged on his own merits.”

Power of One Voice

The rabbi’s powerful statement recognizing the potential goodness within people and stressing his refusal to boycott the team if Trautmann is hired, is greeted with joy by the team’s management and is an obvious step forward in the healing and reconciliation process. It also shows the strength of one voice and the power of the press.

It would have been interesting to see how Rosenmüller and his colleagues might have handled the inner thought process undergone by Rabbi Altmann in reaching his conclusion. In any case, Rosenmüller makes clear that all the bridgebuilding undertaken by Trautmann throughout his soccer-playing years and beyond would have been impossible without the positive interference of the rabbi.

When asked about this during an interview, Rosenmüller called Rabbi Altmann’s letter “the heart of my film.”

“Rabbi Altmann has a role-model function. He judges people not according to their nationality, but according to their individual actions,” he said.

Powerful Story

Rosenmüller is convinced The Keeper is a story about “a brainwashed man who had the chance to realize he was on the wrong path and changed his attitude and his life.”

While there is evidence from the real Trautmann’s post-soccer life that seems to bear that interpretation out, the truth about the sort of people he and his British admirers really were will forever be obscured by history. Did British soccer fans learn to love Trautmann because they forgave him, or simply because they respected a winner? Did Trautmann really have a change of heart (as the film implies) or did he in fact simply learn where his bread would best be buttered?

When the film is taken on its own merits, it doesn’t matter. It is a powerful story about forgiveness. “Bert is someone doing his best to put the past behind him,” says Margaret.

In a time of civil unrest, it is a parable worth considering.

***

Two Sues on the Aisle bases its ratings on how many challahs it pays to buy (rather than make) in order to see the play, show, film, or exhibit being reviewed.

“The Keeper” received 5 challahs