One Man’s Vision of the Future of New York City and the People He Holds Responsible

By Sue Weston and Susie Rosenbluth, Two Sues on the Aisle

If New York City’s political leaders were to adopt the vision of Jason Haber, one of the city’s preeminent realtors, New York might become much more welcoming to undocumented migrants than to those whose tax-dollars have, over the years, helped make it one of the most vibrant urban center in the world. In fact, Mr. Haber might not mind a bit if the city gave up its police force in favor of something that he inferred would consist of residents deciding to band together to keep each other safe.

A reputed expert on New York City’s history and a frequent commentator on CNBC and Fox Business News, Mr. Haber made his remarks on August 10 in a Zoom talk entitled “Peril and Promise: Exploring NYC’s Next Chapter,” sponsored by the Lower East Side Jewish Conservancy (LESJC).

Convinced that, left unchecked, history has a way of repeating itself, Mr. Haber began his talk with a series of photos from 1918 when New York and the rest of the world battled the Spanish Flu. The similarities with the current COVID pandemic were striking. People wore facemasks, there were efforts at contact tracing, and field hospitals were constructed.

1918 Guidelines

Mr. Haber explained that after a Norwegian Steamer introduced the virus to the city, its Health Commissioner, Roy Kopland, who went on to become a US Senator, did not insist on completely shutting down the theaters showing the silent movies that had people enthralled. But he did understand the importance of keeping people separated, directing theaters to fill only half the house and leave an empty seat between each patron.

He even banned smoking in movie theaters, perhaps hoping to eliminate the virus embedded in exhaled breath.

Mr. Kopland insisted on staggering work hours to avoid crowding on the subways, but he kept the schools open. It wasn’t that he was overly concerned about the pace of children’s learning, rather he worried about the lack of sanitary conditions rampant throughout the city’s many tenements in which poorer schoolchildren lived.

Facemasks

The commonalities between the 1918 pandemic and the current environment include a silent spring followed by an angry summer, filled with civil rights protests. In 1918, a vocal minority often risked going to jail rather than wear facemasks, and many were charged with “disturbing the peace” and fined five dollars. The protesters retaliated by forming the Anti-Mask League, whose first meeting in San Francisco attracted two thousand people.

Some Christian Scientists claimed their faith kept them immune from the Spanish Flu and, therefore, they said, they should not have to wear masks. At least two synagogues in Cleveland decided to hold some small services in defiance of the city’s order, which prompted police to arrest some of the worshippers.

Throughout the United States, masks were called “muzzles,” “germ shields,” and “dirt traps.” Some people snipped holes in their masks to smoke cigars (which some cities accepted as a permissible reason, much like eating, to take off the masks). Bandits used them to rob banks with impunity in much the way some antifa mobs use them to engage in insurrection and violence today.

If Mr. Haber has his way, post-COVID New York will have many fewer cars and many more subsidized housing units, although he did not say where the city would find the funds to pay for more efficient—and safe—public transportation or public housing. He knows the money will not come from wealthy New Yorkers who he recognized are fleeing the city in droves. In fact, Mr. Haber favors encouraging free and open immigration to take up the slack created by the exodus from the city.

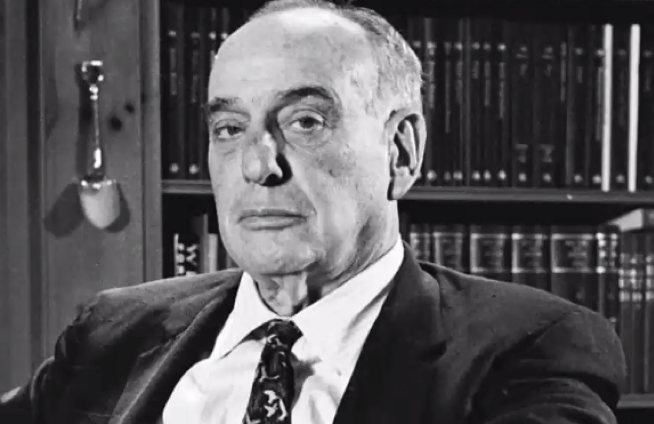

The Villain: Robert Moses

In Mr. Haber’s narrative, there is a historical villain in whose turpitude and immorality lie the roots of all that is wrong with New York. For Mr. Haber, this scoundrel is the controversial Robert Moses, known widely as the “master builder” of mid-20th century New York City and surrounding areas of Long Island and Rockland and Westchester Counties.

Mr. Moses’s decisions favoring highways over public transportation helped create many of New York’s modern suburbs, created a great deal of New York City’s public housing projects, and opened bridges and tunnels, including the Triborough, linking the Bronx, Manhattan, and Queens; the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, connecting Brooklyn to lower Manhattan; and the Throgs Neck, Bronx-Whitestone, and Verrazzano-Narrows Bridges.

In all, Mr. Moses, who was born to secular German-Jewish parents in 1988 and, after graduating from Yale and Oxford, converted to Episcopal Christianity, transformed New York City’s landscape. He was responsible for constructing 35 highways, 12 bridges, numerous parks, Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, and Shea Stadium. After the Second World War, he lobbied hard (and secured the funding) for the fledgling United Nations to build its headquarters in Manhattan rather than in Philadelphia.

Over the years, he held a dozen offices and professional titles, many of them simultaneously, ranging from president of the Long Island State Park Commission, chairman of the Emergency Public Works Commission, head of the NYC Planning Commission, chairman of the NY State Power Authority, and Special Advisor on Housing to the Governor of New York.

When he died in 1981, the funeral was held at St Peter’s by the Sea Episcopal Church which, according to the New York Times obituary, was “surrounded by examples of the bridges, causeways, and parkland he left as his legacy.”

Polarizing Racism

Although Mr. Haber did not mention it, many of Mr. Moses’s projects were widely considered necessary for the region’s development. He was actively involved in New York politics from 1927, when he was appointed New York’s Secretary of State, to 1975, but, even in his own time, he was recognized as one of the most polarizing figures in the history of urban development. In his talk for the LESJC, Mr. Haber capitalized on Mr. Moses’s negatives, which included a reputation for lust for power, questionable ethics, vindictiveness, and racism.

For example, in the late 1930s, Mr. Moses oversaw the building of the campus to host the 1930 World’s Fair at Flushing Meadows-Corona Park in Queens. Mr. Haber pointed out that a highlight of the fair was its Futurama exhibit in which planners, led by Mr. Moses, envisioned a world dominated by the automobile. For Mr. Haber, it meant a design for “congestion” which, he said, “prioritized cars over people.”

Further, said Mr. Haber, his support for segregation was manifest in that the roads he created were purposely designed to be unsuitable for buses or any mass transportation.

“He did not want minorities, who did not own cars and would have to arrive by bus, to travel across his parkways,” said Mr. Haber.

This was particularly true of Jones Beach, Mr. Moses’s centerpiece of the Long Island state park system. Among the measures taken by Mr. Moses to keep Jones Beach “white” were making it difficult for black groups to obtain permits to park buses even if they managed to come by using other roads and assigning black lifeguards to other, less developed beaches.

Again left out of Mr. Haber’s talk was the fact that Mr. Moses, working with then-Mayor Fiorello H. LaGuardia, was responsible for the construction of ten gigantic swimming pools. Combined, they could accommodate some 66,000 swimmers. But Mr. Moses demanded that the water temperature be kept a few degrees colder than normal in the bizarre belief that African-Americans did not like cold water and, thus, would steer clear of the pools.

Stuyvesant Town

During World War II, Mr. Moses, at the behest of Mayor LaGuardia, championed the construction of what may have been the first urban renewal project. Stuyvesant Town was built to be a post-war middle-class residential development on the remnants of the “Gashouse District” (named after the many gas storage tanks that had been on the site) in Manhattan and financed by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company.

For many reasons, Stuyvesant Town was controversial from the start. Veterans were given selection priority for the development’s modestly priced apartments, but an effort led by Mr. Moses barred African-American soldiers’ families from participating. Although Mr. Moses had, by that time, disassociated himself from the Jewish community, Mr. Haber made clear that Stuyvesant Town was, from the beginning, open to Jewish families, many of whom rushed to apply for apartments.

Mr. Moses was convinced that African-Americans would harm the profitability of Stuyvesant Town, and Metropolitan Life agreed. In an effort to install separate-but-equal housing in New York, Metropolitan Life built the Riverton Houses housing project in Harlem specifically for African-Americans.

According to Mr. Haber, very soon after Stuyvesant Town opened, a few unsuccessful protests were mounted to open the development to African-Americans, and Jews, most of them residents of the complex, were at the forefront of that effort to reverse the racist policy.

For Mr. Haber, Mr. Moses’s sins of racism and predilection for automobile congestion prevent anything favorable to be said on his behalf. When asked, Mr. Haber reluctantly admitted that Mr. Moses’s prejudices may have reflected the time in which he lived.

“Let’s just say he was not on the right side of history,” said Mr. Haber.

Jane Jacobs

But Mr. Haber did have a heroine, Jane Jacobs, a journalist and social activist who championed building community-based cities. Despite her last name, Mrs. Jacobs was not Jewish. She was born in Scranton, Pennsylvania, in 1916, and, as an adult, fell in love with New York City’s Greenwich Village. Her husband was Robert Hyde Jacobs, Jr, a Columbia-educated architect.

After World War II, the Jacobses rejected the rapidly growing suburbs as “parasitic” and chose to remain in Manhattan, where she made a name for herself as an opponent of urban planning. She organized grassroots efforts to protect neighborhoods from Mr. Moses’s urban renewal/slum clearance efforts and especially his plans to overhaul Greenwich Village.

She was instrumental in the cancellation of Mr. Moses’s Lower Manhattan Expressway, which would have run through that area of the city and connected to several tunnels and bridges. It would have separated neighborhoods, such as SoHo and Little Italy, and resulted in the destruction of hundreds of buildings and the eviction of thousands of families.

Mr. Haber characterized her as a promoter of higher-density within cities, which she envisioned as places with short blocks that supported local economies. He admired her passion against Mr. Moses’s car-centered view of urban planning.

Post-COVID Future

After Mr. Haber’s talk, the evening exploded into a conversation about the changing streetscape of New York in the months of the COVID pandemic. Most participants recognized that the shutdowns coupled by the protests, which have often devolved into violence and other acts of civil disobedience, as well as the skyrocketing crime rate have discouraged tourists and potential residents from coming to NYC.

Other changes include the loss of multigenerational extended families and the introduction of transient NYC residents, some of them homeless and others attracted by lower rents.

New York moving companies say they are inundated with requests from people who are leaving the city permanently. United Van Lines released data showing a 95 percent increase in interest in moving out of Manhattan.

Although the LESJC’s mission has been to preserve and share the Jewish history and heritage of the Lower East Side, the group has recently expanded its scope to explore the migration of the Jewish population, and its in-person tours are scheduled to resume in the fall.

Mr. Haber’s talk did not include Jewish history or the migration that took place, some of it because of Mr. Moses’s efforts, and the lecture might have been better had he discussed the history without promoting his own opinions as the definitive point of view. All people have virtues and vices; all have feet of clay. It would have been helpful if he had discussed the pros and cons of the personalities he included in his program.

***

Two Sues on the Aisle bases its ratings on how many challahs it pays to buy (rather than make) in order to see the play, show, film, or exhibit being reviewed.

“Peril and Promise: Exploring NYC’s Next Chapter,” received 3 Challahs