Europeans Honor Righteous Gentile Sousa Mendes: Risking for Principles of Conscience

By Sue Weston and Susie Rosenbluth – Two Sues on the Aisle

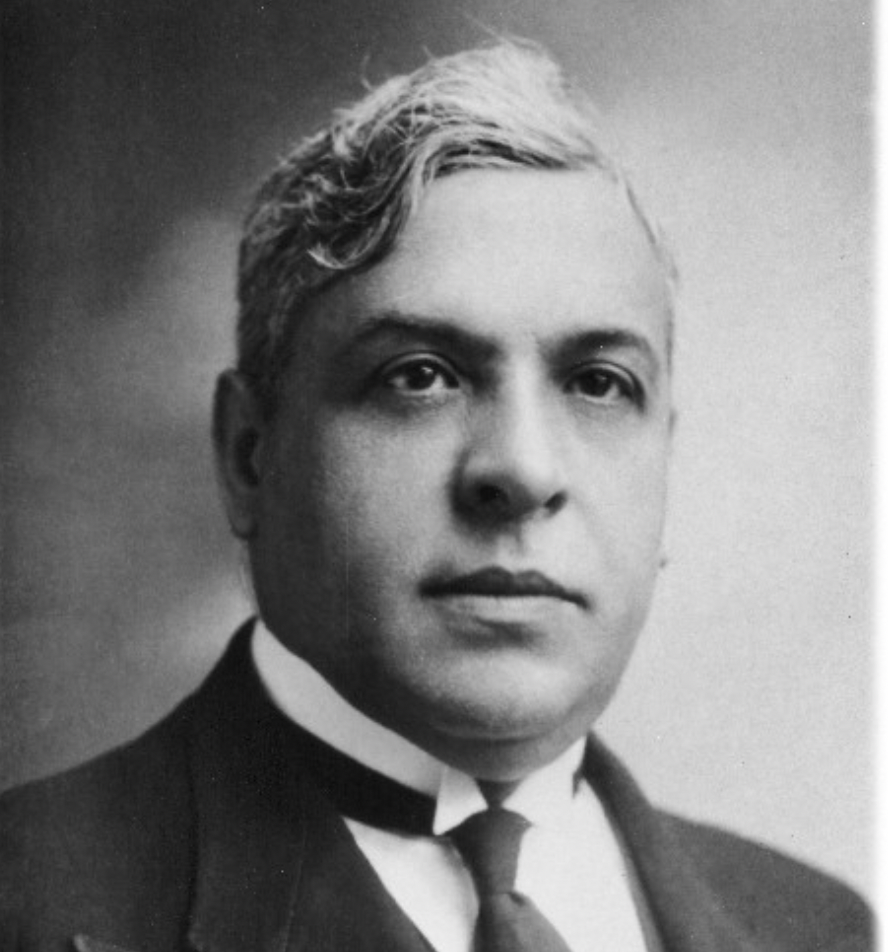

This past March 6, European Day of the Righteous, Holocaust rescuer Aristides de Sousa Mendes, a Portuguese diplomat stationed in France in 1940, was inducted into the Garden of the Righteous in Milan, Italy. In so doing, the Milan-based group joined dozens of others that have honored Sousa Mendes, who singlehandedly issued 30,000 visas—10,000 of them to Jews—allowing their bearers to flee from the Nazis and gain safe passage through Spain to Lisbon.

The Garden of the Righteous, the European equivalent of Yad Vashem, is committed to recognizing acts of humanity and people who have tried or are trying to prevent crimes of genocide. The group seeks to defend human rights and safeguard memory from the recurring attempts to deny the truth about the persecutions.

Among those most gratified by the efforts of all groups that have recognized the bravery and dedication of Sousa Mendes is the foundation that bears his name. Since 2010, the Sousa Mendes Foundation has taken as its mission honoring Aristides de Sousa Mendes and educating the world about his activities and valor, acknowledged as one of the largest rescue actions by a single individual during the Holocaust.

The foundation is aware that as witnesses and survivors age, the burden of reminding the world falls on the next generation. To that end, the Sousa Mendes Foundation, through its various programs and website, is determined to show how this one man, ignited by his own deeply ingrained religious beliefs, fought against intolerance and wholesale murder. He simply could not stand by while men, women, and children died before his eyes.

Defying His Own Government

Born in 1885 to a highly respected Portuguese family, Aristides de Sousa Mendes do Amaral e Abranches was a career diplomat, serving his country in posts throughout the world, including Europe, Africa, and North and South America. In 1938, he was appointed Portuguese Consul-General in Bordeaux, France, and he relocated there with his family, including his wife and their 15 children.

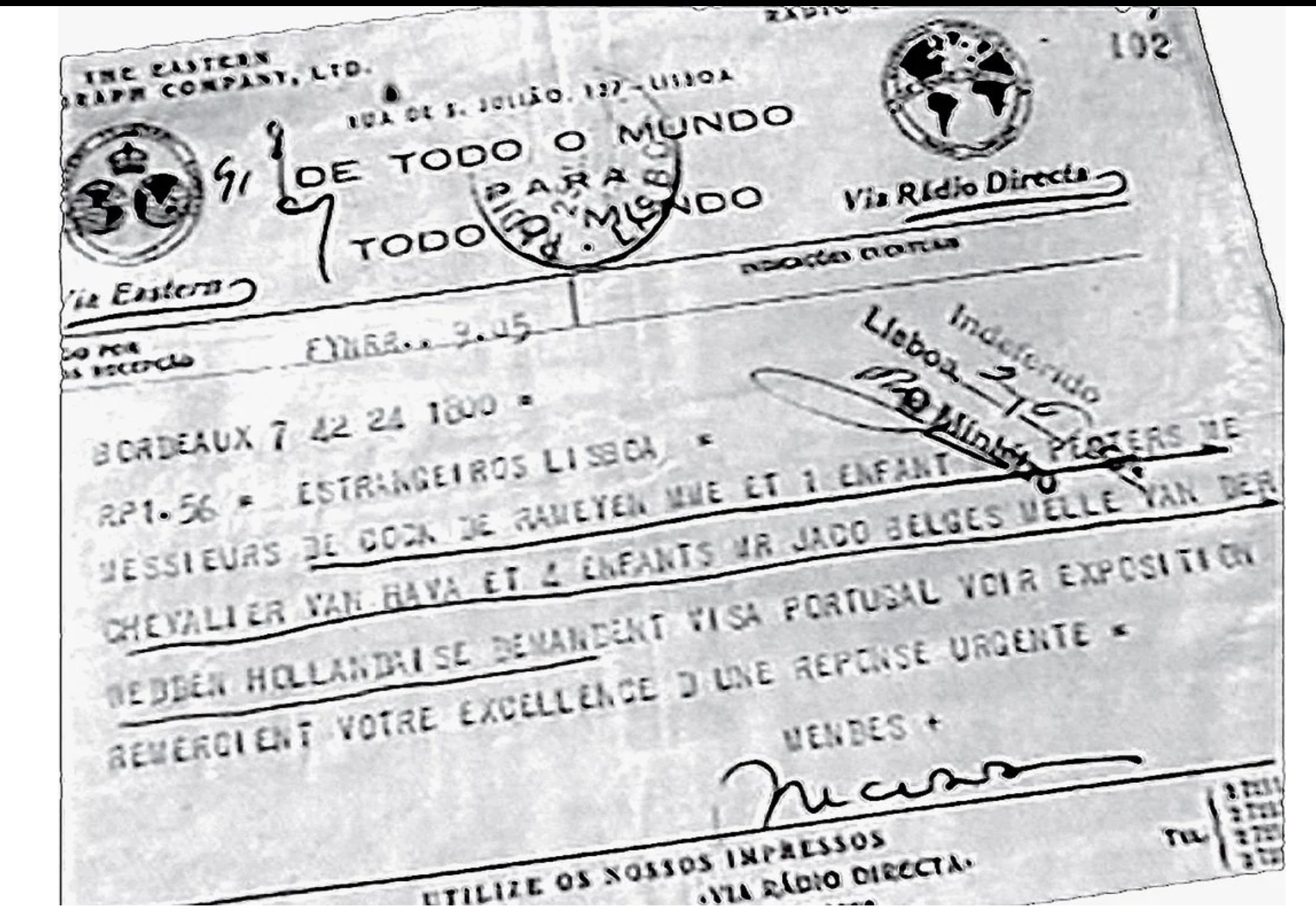

A year later, Germany invaded Poland, and in November 1939, Sousa Mendes’ government, headed by the dictator, Antonio de Oliveira Salazar, issued its notorious directive known as Circular 14. It forbade Portuguese consular officials from issuing Portuguese visas to refugees from Nazism. The directive singled out Jews and “stateless persons,” referring to them as people who would not be able to return to their home countries.

Initially, the then-54-year-old Sousa Mendes did what he could to provide shelter to elderly and infirm refugees, but by June 1940, the need for visas to get out of France became desperate. Faced with thousands of refugees lining up outside the Portuguese consulate, he began acting in direct violation of Circular 14, earning himself a sharp rebuke from his superiors. In a letter to his brother, Sousa Mendes said of Salazar, “The Portuguese Stalin decided to pounce on me like a wild beast.”

Although officially Salazar’s Portugal was neutral, it was unofficially very pro-Hitler.

Signing Visas En Masse

When Sousa Mendes’ formal request to issue visas was rejected, he took it upon himself to issue the life-saving passes that would entitle the holders to travel into Spain and on to Portugal. He threw open the doors to the consulate and began signing visas en masse. Refugees, many of them Jews, lined up by the thousands at his desk, and the file extended out the door, down the stairs, and into the street.

“Add to this spectacle hundreds of children who were with their parents and shared their suffering and anguish,” Sousa Mendes wrote. “All this could not fail to impress me vividly, I who am the head of a family and better than anyone understand what it means not to be able to protect family.”

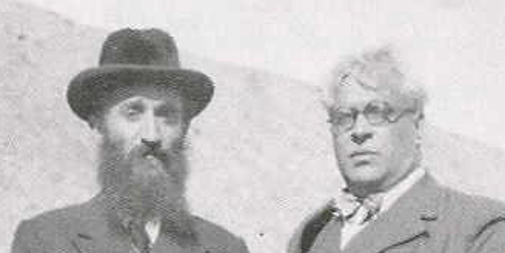

Among those he saved was Polish Rabbi Chaim Kruger along with his wife and five children. When Sousa Mendes managed to get a visa for the family, Rabbi Kruger insisted he couldn’t possibly leave unless all his fellow Jews waiting outside the consulate were given visas, too.

According to some reports, Sousa Mendes replied to the rabbi, “You win” and began signing even more visas. The Portuguese diplomat realized he had a choice: he could obey his government or obey his conscience. He chose the latter.

“I would rather stand with G-d against man than with man against G-d,” he is reported to have said, citing his Christian conscience.

Saving Lives in Bayonne

About nine days after he began his visa operation, he had already saved thousands of lives. However, he received word that similarly, desperate scenes were taking place outside the Portuguese consulate further south, and he instructed Portugal’s vice-consul in Toulouse to begin issuing visas there.

Sousa Mendes himself rushed to Bayonne, near the Spanish border, where thousands were waiting in the streets for him. “On my arrival, there were so many thousands of people, about 5,000 in the street, day and night, without moving, waiting their turn,” Sousa Mendes later recalled. There were “about 20,000 all told, waiting to get to the consulate,” he said.

According to reports, he set up a table outside and signed every passport for this group of refugees which included H.A. and Margret Rey, who had escaped from Paris with an illustrated manuscript of what was to become their celebrated children’s book, Curious George.

Saving Future Celebrities

Other notables among those rescued by Sousa Mendes include the banking magnates Edward, Eugene, Henri, and Maurice de Rothschild. Gala Dalí, the wife of the artist Salvador Dali, requested visas for herself and her husband.

Actors Israel and Madeleine Blauschild—better known by their screen names, Marcel Dalio and Madeleine LeBeau—sought and received help from Sousa Mendes after the Nazis plastered images of Dalio’s picture throughout France, labeling him a “typical Jew.” In 1942, the couple appeared in Casablanca, a film about refugees seeking letters of transit to Portugal. Dalio portrayed the croupier Emil, and Le Beau was the young singer who belted out La Marseillaise while tears ran down her face.

On June 22, Sousa Mendes heard from Salazar directly, forbidding him to grant visas for anyone to enter Portugal. This left some 10,000 refugees stranded in Nazi-occupied France.

Although Sousa Mendes was ordered to return to Bordeaux, he instead went to Hendaye, a French seaside town along the Spanish border, where he found hundreds of refugees unable to pass into Spain because visas he had issued had been declared “null and void.” Among the refugees, he spotted Rabbi Kruger and his family, who had been stopped by the guards. Sousa Mendes negotiated with the guards himself for over an hour. When he was through, he opened the gate himself and waved the rabbi and all the refugees with him across the border to safety.

Punished by the Regime

On June 24, 1940, Sousa Mendes was recalled to Portugal, and on July 4, disciplinary proceedings against him began. The verdict had been decided in advance. Sousa Mendes was forced to retire, and although he had been promised a pension, he never received it.

Ruined, Sousa Mendes lost everything. His children were blacklisted, prevented from finding work or attending school in Portugal, and the family was reduced to poverty. Even his family’s ancestral home, Caso do Passal, was repossessed to repay debts. Many of his children, fearful of retribution scattered across the globe.

According to sources, he accepted his fate with a modicum of equanimity. “The only way I can respect my faith as a Christian is to act in accordance with the dictates of my conscience. I could not have acted otherwise, and I, therefore, accept all that has befallen me with love.”

Eating with Fellow Refugees

By 1942, he and his family were taking meals at a Jewish community soup kitchen in Lisbon, Cozinha Económica Israelita, which had two rooms, one for Portuguese families and the other for refugees. Sousa Mendes chose to eat with the refugees, telling his fellow diners, “We, too, are refugees.”

According to some sources, Sousa Mendes suspected that although he was a devout Catholic by faith, he may have been a descendant of conversos, Jews who had been forced to convert during the Spanish and Portuguese Inquisitions.

Over the next several years, Sousa Mendes tried vainly to improve his situation, asking for reinstatement or, at the very least, to gain access to his pension. Pope Pius XII, who did nothing to help the Jews during the Holocaust, also turned down his request for assistance.

Opportunists

Ironically, as the war wound down and Salazar realized an Allied victory was in the offing, his regime tried to take credit for Sousa Mendes’ actions on behalf of refugees. In a speech to the Portuguese National Assembly, he said, “What a pity that we could not do more.”

In the summer of 1945, Sousa Mendes suffered a stroke, leaving him unable to continue his quest to clear his name. Nine years later, he died at the age of 68. According to reports, on his deathbed, he told a nephew that he took solace in the knowledge that although he had nothing but his name to leave his family, the name was “clean.”

He did, however, also ask his children to continue his efforts to clear his name and restore the family’s honor.

Jewish Efforts

That was no easy task. After Sousa Mendes’ death, the Salazar regime did its best to erase Sousa Mendes’ name from the records. Great efforts seemed to have been made to ensure that the Portuguese knew little or nothing about the refugees who had passed through their country. But Sousa Mendes’ children took up the cause, urging Jewish leaders in Portugal, Israel, and the United States to recognize what their father had done.

In 1961, Israel’s Prime Minister, David Ben-Gurion, ordered 20 trees planted in Sousa Mendes’ name. In 1966 Yad Vashem declared him one of the “Righteous Among the Nations.”

In 1970, Salazar died, and the authoritarian regime he established was overthrown. Portugal’s new government commissioned a report about Sousa Mendes, and the findings were scathing. It called the treatment he had received by his own government “a new Inquisition.” But it took another decade before anything was done about it.

American Efforts

In 1986, some 70 US Congressmen and Senators signed a letter to Portugal’s president, Mario Soares, urging him to recognize Sousa Mendes’ actions and valor, and a year later, the US House of Representatives passed a resolution honoring his heroism and him for “remaining faithful to the dictates of his conscience.”

At a ceremony held that year at the Portuguese Embassy in Washington, DC, Soares, on behalf of his government, apologized to the Sousa Mendes family.

Finally, in 1988, the Portuguese Parliament officially dismissed the charges against Sousa Mendes and promoted him to the rank of ambassador.

In 1995, Soares proclaimed Sousa Mendes “Portugal’s greatest hero of the twentieth century.”

Stories of the Righteous

When the Garden of the Righteous honored Sousa Mendes this past March, it did so as part of the group’s 2022 theme: “Preventing genocides and mass atrocities. The stories of the Righteous against silence and indifference.”

The Sousa Mendes Foundation provides a wide array of programming, documentaries, and interviews. The foundation continues to chronicle and share stories of survivors and Righteous Gentiles and has compiled a list of more than 3,800 of the Sousa Mendes’ visa recipients from over 49 countries. Lend your voice to help perpetuate the memory of Aristide de Sousa Mendes, by donating, volunteering, or participating in programming.