Warder Cresson was Accused of Being Insane for Converting to Judaism

by Rabbi Menachem Levine

The prominent Quaker opened America’s first consul to Jerusalem. After converting and returning home, he was put on trial for insanity.

Warder Cresson was born to a prominent Quaker family in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on July 13, 1798. Members of his family were successful artisans and entrepreneurs and owned prime real estate in the center of Philadelphia, as well as farmland in the surrounding countryside.

When he was seventeen, Warder went to work on the family farms. Within a few years, he became the head of a very successful farming enterprise.

Yet Warder had interests beyond agriculture and finances. In 1827, began to publicly question some of the fundamental tenets of Quakerism, and he did so in writing. In his first religious tract, An Humble and Affectionate Address to the Select Members of the Abington Quarterly Meeting, he criticized the religious leaders of his day while showing both his knowledge of Scriptures, as well as his grasp of the social issues of his time.

In 1830 he published a pamphlet bemoaning the extravagance and misdeeds of those around him and exhorted all Quakers to lead a better and more focused life.

Around this time, he went through a period of great religious upheaval. He left Quakerism and joined one sect after another. By 1840 he had become, in turn, a Shaker, a Mormon, a Seventh-Day Adventist, and a Campbellite.

Connection to Judaism

Cresson eventually found his way to Mikveh Israel, Philadelphia’s leading Jewish congregation where he received a warm welcome from the influential Orthodox scholar, Chazzan Isaac Leeser. Chazzan Leeser discussed a broad range of topics with Cresson and taught him the Jewish interpretations of passages in the Bible and Judaism’s description of the Messiah. Through Chazzan Leeser, Cresson also began reading the writings of Mordecai Manuel Noah, a leading Jewish political leader who pushed the American government to commit to supporting the reestablishment of a Jewish homeland in the Middle East. He felt that this alone would solve the issue of antisemitism. Noah’s writings began to influence Cresson’s views on the land of Israel and would continue to impact him in the coming years.

During the 19th century, there were many Christian Americans who were disappointed that the salvation they had expected had not occurred in America and they now turned to the land of Israel, looking for salvation to come from that direction. This was theologically supported by a belief that for Christianity to flourish and for their leader to return and save all of humanity, the Jews must return to their historical homeland. (This belief continues amongst many pro-Israel Christian groups today and is a point of contention to some who question their support.)

First American Consul to Jerusalem

Cresson used his influence to persuade a Philadelphia congressman named Edward Joy Morris to suggest he be appointed America’s first consul to Jerusalem. There had never yet been a consul to Jerusalem because at that time the city had barely 15,000 people living there! Yet, its renown as the Holy City and the fact that the American pilgrims and missionaries who visited would benefit from a diplomatic outpost led Morris to contact Secretary of State John C. Calhoun and ask for Cresson to become the consul. He also made it clear that Cresson intended to work at no cost to the government, but would rely on his personal fortune for his needs.

The State Department agreed and officially appointed him on May 17, 1844. Cresson left his family in America and set sail for Jerusalem. He wrote in his diary at the time of his departure: “In the Spring of 1844, I left everything near and dear to me on earth. I left the wife of my youth and six lovely children (dearer to me than my natural life), and an excellent farm, with everything comfortable around me. I left all these in the pursuit of truth, and for the sake of Truth alone.”

But complaints and criticisms were heard regarding his appointment. Some felt he was not a trustworthy or fitting diplomat, due to his well-known strong religious views. As a result, Calhoun rescinded the appointment by writing to Cresson and letting him know in President John Tyler’s name, that the government had chosen not to establish a consulate in Jerusalem and he was therefore no longer the consul.

Cresson, however, had already set sail for the Holy Land and wasn’t aware of his change in status. He proudly disembarked with flourish in Jaffa, holding an American flag in one hand and a symbolic dove in a cage in his other.

He began establishing himself in earnest as the consul. He created a new consular seal to use in his correspondence as the representative of the United States. He also announced to the Jews of Jerusalem that in his role as consul, he would ensure they were now under the protection of the American government. It was at this time that he received word from Calhoun that his appointment as consul had been rescinded.

With a firm belief in his mission, Cresson disregarded the message and continued to present himself as the American consul in the Holy Land. Neither the Turkish authorities nor the distant American government acted to stop him. He was free to act as he wished.

Shortly after his arrival, Cresson penned a glowing piece describing in euphoric terms the ancient but neglected city of Jerusalem that most other visitors viewed as dirty and dilapidated. Jerusalem, the Centre and Joy of the Whole Earth, was published in Philadelphia and London at Cresson’s direction.

Defender of the Jews and New Identity

Though it was originally feared that Cresson’s missionary motives would stir up trouble for the Jews, he instead declared war on the Christian missions that he believed were exploiting the poor Jews of Jerusalem.

Cresson wrote critically of the high salaries paid to the missionaries who lived “in the very best houses, bought most splendid Arabian horses and dressed in the most luxurious and stylish manner.” According to Cresson, the missionaries failed to get a single Jew to apostatize.

Affected by the surroundings of Jerusalem, he became more inclined toward Judaism and assumed the name Michoel C. Boaz Israel. In 1844–1848, he was a frequent contributor to Isaac Leeser’s magazine, The Occident, in which he criticized the missionary tactics of the London Society for Promoting Christianity Amongst the Jews.

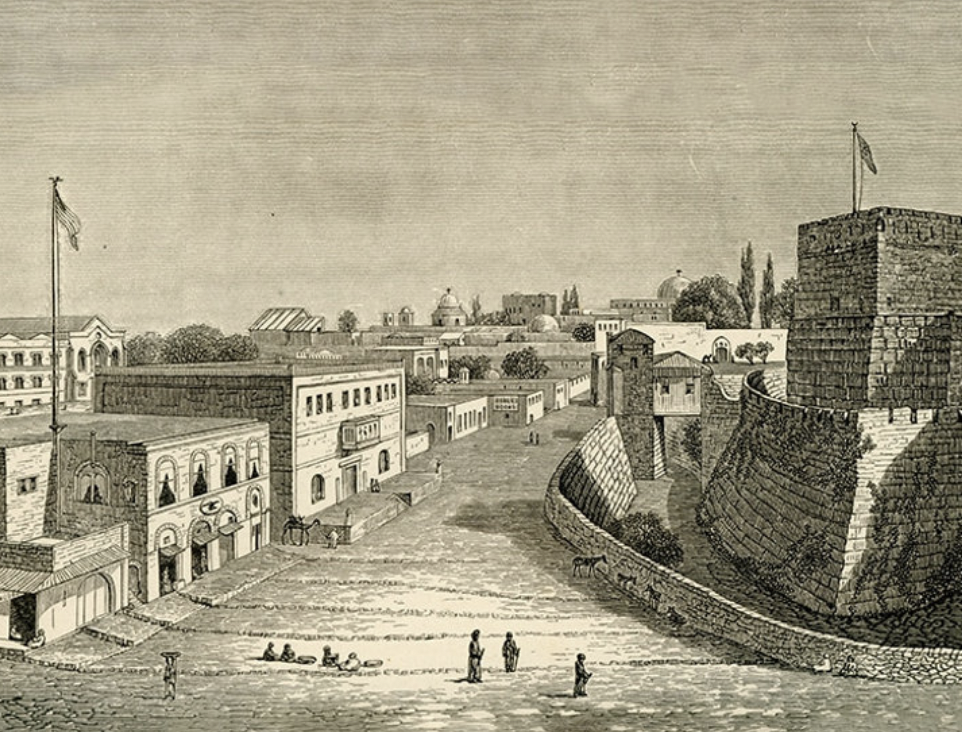

The American flag over the first residence of the American consulate, Jaffa Gate, circa 1857. Frank DeHass 1883 Courtesy MFH TAC Jerusalem LOC Washington Edwin W Holy Jerusalem, 1898

While in Jerusalem he became particularly close to the Sephardic community, including the future Sephardic chief rabbi, Harav Yaakov Shaul Elyashar.

In 1847, Cresson began writing, “The Key of David the True Messiah”, in which he began his journey towards Judaism, denying the divinity of Jesus. Cresson was ready for the final step of his spiritual journey and the most consequential decision of a turbulent life.

He writes, “I remained in Jerusalem in my former faith until the 28th day of March 1848 when I became fully satisfied that I could never obtain Strength and Rest, but by doing as Ruth did, and saying to her Mother-in-Law, or Naomi ‘Entreat me not to leave thee for whither thou goest I will go’… In short, upon the 28th day of March 1848, I was circumcised, entered the Holy Covenant, and became a Jew.”

Trial for Insanity

Throughout this transition, Cresson had been writing to his wife and children to keep them informed of his spiritual progress—and of his new name, Michoel Boaz Israel ben Avraham. He had no desire to abandon the family that he “loved most dearly above anything else on earth” and felt certain that he could persuade them to share the satisfaction of his new faith and to return with him to his mission in Zion.

Sailing back to Philadelphia in September 1848, Cresson received a devastating reception. He was informed that his wife, Elizabeth, had taken sole possession of their property and sold off the family farm as well as Warder’s personal effects. She ignored his appeals for a settlement and joined other family members in lodging a formal charge of “lunacy” against him for his conversion.

Cresson’s conversion to Judaism was considered so eccentric and bizarre that his non-Jewish family had him brought up on charges of insanity. A “sheriff’s jury” of six men quickly agreed with their arguments and issued its verdict of insanity, but Cresson, who never spent a day in an insane asylum, challenged their decision in court.

The resulting trial lasted for almost three years, included more than one hundred witnesses, and became a national sensation. Aside from the obvious attempt by a frustrated and embittered wife to seize what remained of her wandering husband’s wealth, the dispute involved the government’s power to stigmatize and punish a citizen’s midlife decision to embrace an ancient faith. Cresson fiercely defended his right to select his own religious path, no matter how exotic or inexplicable its practices might seem to his former neighbors.

Esteemed physicians, theologians, and legal scholars gave testimony on both sides. While no one denied Cresson’s reputation as “a strange bird” (in the words of one correspondent), the leaders of the nation’s small Jewish community testified on his behalf, resisting the notion that conversion to Judaism in any way constituted natural proof of insanity. Cresson’s lawyer, the distinguished Horatio Hubbell Jr., characterized the case as a critical test of the religious liberty guaranteed by the First Amendment. His closing statement ended with a dramatic denunciation of the attempt to discredit an unconventional thinker based on his religious ideas alone. “The only charge left with which to accuse my client,” he thundered, “is that he became a Jew!”

By that time, the newspapers covering the trial had swung in support of Cresson’s cause and they unanimously expressed their euphoria at his vindication. Philadelphia’s Public Ledger saw the decision as “settling forever … the principle that a man’s ‘religious opinions’ never can be made the test of his sanity.”

Eventually, Cresson ended up leaving most of his property to his family and returned to Jerusalem in 1852.

Return to Israel and Agricultural colony in Palestine

Upon his return, Cresson became involved in actively supporting efforts towards the agricultural regeneration of Palestine by the Jewish Settlement. His goal was to reduce the dependency of the Jews on Christian charities in the hopes of making the Jewish Settlement as self-sufficient as possible. He well knew that the Christian institutions were mainly interested in converting the Jews away from Judaism and that poverty could create vulnerability for the Jews.

In the fall of 1852, while Sir Moses Montefiore and American businessman and philanthropist, Judah Touro, were working along the same lines, Cresson announced his intention of establishing an agricultural colony in Emek Refaim.

In March 1853, he published a column in “The Occident” and sent a circular from Jerusalem soliciting assistance for his projects. But it appears that he was never able to raise the necessary funds.

Last Years

Cresson made a new life for himself in Israel and lived as an Orthodox Sephardi Jew. He became a prominent leader in the Jewish community. His second marriage was to a woman named Rachel Moledano and together they had two children, Abigail Ruth, and Dovid Ben-Zion. Unfortunately, both of them died young and he had no other Jewish descendants.

On the day of his passing, November 6, 1860, all the places of business in Jerusalem were closed out of respect, and the entire Jewish community attended his funeral. He was buried on The Mount of Olives, but without descendants to tend to his gravesite, its location, like memories of the consul’s remarkable role, was lost to history for some five generations. In 2013 Cresson’s lost gravesite was rediscovered and it was once again possible to visit his grave and give proper honor to this exceptional individual.

Rabbi Menachem Levine is the CEO of JDBY-YTT, the largest Jewish school in the Midwest. He served as Rabbi of Congregation Am Echad in San Jose, CA from 2007 – 2020.