The Progressive Era – History that Repeats

By Sue Weston and Susie Rosenbluth – Two Sues on the Aisle

History repeats itself, suggests author Paul Kaplan, whose specialty is recurring patterns impacting New York. Kaplan’s book, New York in the Progressive Era: Social Reform and Cultural Upheaval from 1890-1920, provides context to a journey back in time, exploring social movements, reforms, and their impact on life. Kaplan provides parallels between the present and a century ago, a launchpad for exploring similarities with the Progressive Era. While the title of his latest book is long, his recent book talk was a laser-focused, engaging session sponsored by the Lower East Side Jewish Conservancy (LESJC), a non-profit organization dedicated to the historic preservation and revitalization of the Jewish experience.

Kaplan is no stranger to the LESJC. A former board member, he previously presented a virtual book tour about the Rise and Fall of New York’s Penn Station. A graduate of Yale with a BA in Ethics, Politics, and Economics and an MBA from the School of Management, he is a master presenter who has given over 50 talks globally. While his career has been focused on marketing content thought leadership, digital media, and product strategy, he is an accomplished author (whose books include Jewish New York and Jewish Florida).

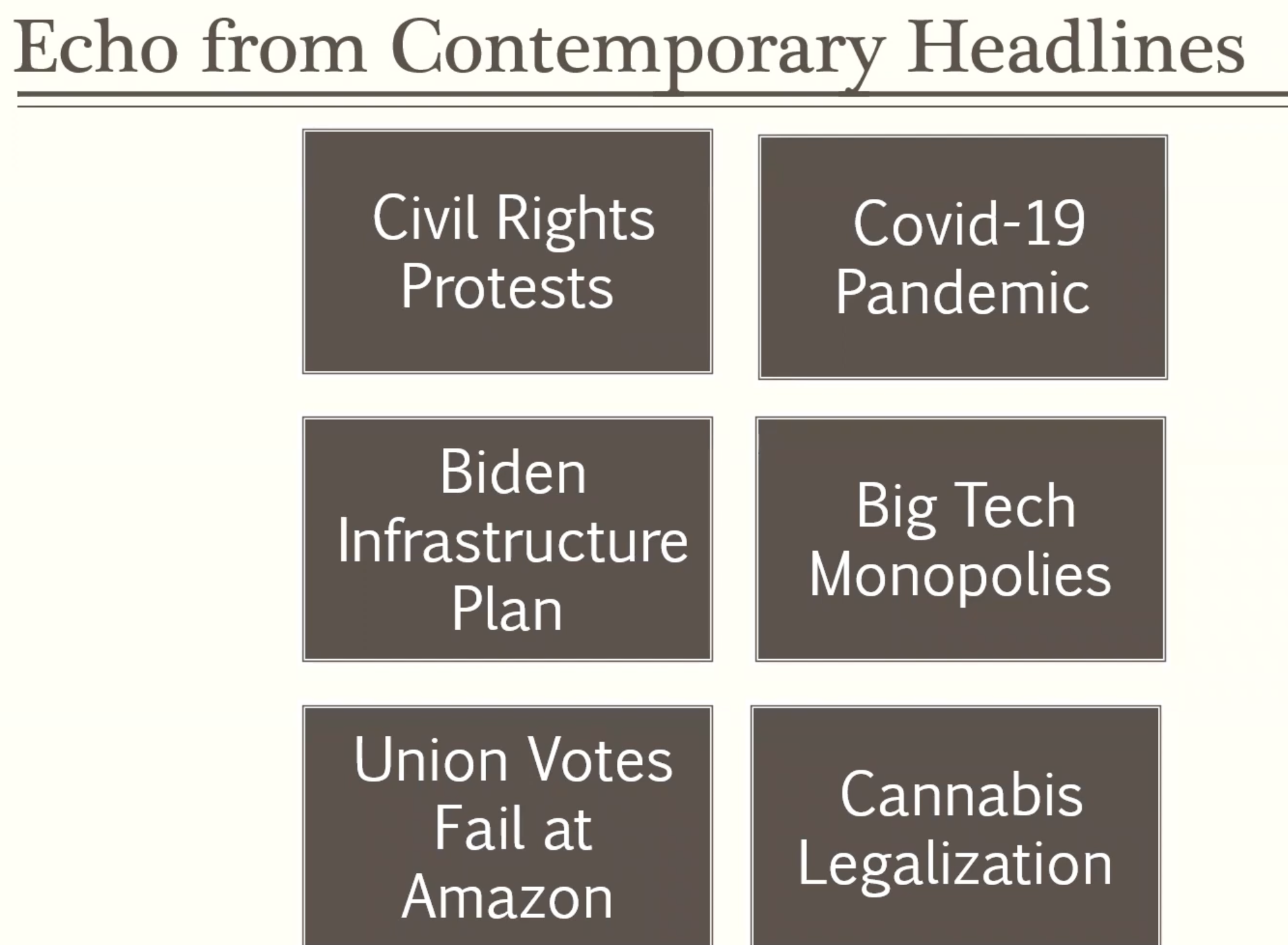

At the LESJC program, Kaplan masterfully leveraged his broad knowledge base as he focused this discussion on a range of recurring topics, including infrastructure, civil rights protests, monopolies, gender inequality, taxes, environmental issues, prohibition, and a pandemic. Sounds like everything old is new again, especially with an experienced eye guiding us, pointing out the connections.  Inequality Prompts Social Reform

Inequality Prompts Social Reform

Describing the era, Kaplan shared a quote attributed to Charles Warner who, with Mark Twain, coined the term the “Gilded Age.” The novel they co-wrote depicts an era during which issues were covered by a thin gold layer, a veneer, to deceive rather than correct the underlying problems. It was, Kaplan said, very much like Warner’s criticism of the way we view the elements: “Everybody complains about the weather, but nobody does anything about it.”

The Gilded Age (which ran from the 1870s to about 1900) was a period of rapid economic growth in the US, a time of prosperity for many. It also widened the gap between the haves and have-nots. But for the most part, the wealthy were unconcerned, believing poverty to be a personal decision attributed to laziness and poor choices.  The Gilded Age set the stage for The Progressive Era (which ran from 1890 to 1920), during which reformers called for social action, passing laws intended to resolve inequities. Several key events included the New York State Legislature’s passage of the Tenement House Act in 1901, Congress’s ratification of the 16th Amendment allowing for personal income tax, and the establishment of prohibition. Kaplan suggests that these reformers may have been too controlling in their attempts to legislate morality. The reformers believed that corrections in private spaces would translate into improvements in public spaces. Their goal was to introduce their cultural norms to the population, without recognizing the misalignment between their interests and that of the emerging working class. As a result, they prioritized parks over dance halls and billiards, and museums over circuses and baseball. They required museums to be open on weekends which made them available to the middle-class.

The Gilded Age set the stage for The Progressive Era (which ran from 1890 to 1920), during which reformers called for social action, passing laws intended to resolve inequities. Several key events included the New York State Legislature’s passage of the Tenement House Act in 1901, Congress’s ratification of the 16th Amendment allowing for personal income tax, and the establishment of prohibition. Kaplan suggests that these reformers may have been too controlling in their attempts to legislate morality. The reformers believed that corrections in private spaces would translate into improvements in public spaces. Their goal was to introduce their cultural norms to the population, without recognizing the misalignment between their interests and that of the emerging working class. As a result, they prioritized parks over dance halls and billiards, and museums over circuses and baseball. They required museums to be open on weekends which made them available to the middle-class.

Where the Past and the Present Connect

Kaplan touched on recurring themes, such as the struggle for social justice, which he connected to the Black Lives Matter movement, and today’s efforts to rebuild the infrastructure, which, he said, parallelled the building of railroads. Anti-monopoly concerns continue to be an issue, as does unionization, underscoring the need to protect workers’ rights. He compared prohibition as a movement to today’s efforts to legalize cannabis. He pointed to the 2011 “Occupy Movement,” whose slogan “We are the 99%,” as a modern-day push to eliminate inequality in the US. Corruption and scandals in politics were rampant then as now. In fact, he said, the Progressive Era might be seen as Americans’ fledgling efforts to gain a social consciousness.

Many observers have agreed that proponents of these movements, then as now, often charge full-steam ahead without considering the unintended consequences that come in their wake.  While common themes appear to be repeating, Kaplan noted there has been a great deal of progress. One example is how scientists’ and doctors’ experience with the Spanish Flu aided researchers faced with having to combat COVID19. Kaplan discussed improvements due to the passage of laws that reformed working conditions, regulated child labor, and upgraded housing conditions. The evolution of the woman’s suffrage movement provided equal access to education, inheritance rights, voting privileges, and employment.

While common themes appear to be repeating, Kaplan noted there has been a great deal of progress. One example is how scientists’ and doctors’ experience with the Spanish Flu aided researchers faced with having to combat COVID19. Kaplan discussed improvements due to the passage of laws that reformed working conditions, regulated child labor, and upgraded housing conditions. The evolution of the woman’s suffrage movement provided equal access to education, inheritance rights, voting privileges, and employment.

Kaplan suggested that the higher wages seen in the roaring ‘20s might have been a consequence of deaths from the Spanish Flu (which he called the Forgotten Virus). He suggested we might be experiencing a similar phenomenon with the Great Resignation, the roughly 33 million Americans who have quit their jobs since the spring of 2021.

Leisure and Quality of Life

The Progressive Era is credited with the emergence of the middle class, city workers with disposable income, and the concept of free time. Improving the middle class’s quality of life became a focal point for reformers, who sought to provide them with wholesome activities, parks, baseball, circuses, and museums that were open on weekends, as well as increasing their exposure to nature through organizations like the Fresh Air Fund.

One legendary leader, notable for her contributions to improving society is Lillian Wald, founder of the Henry Street Settlement to assist the Jewish immigrants of the Lower East Side by providing healthcare, education, and pioneering quality-of-life initiatives. The Settlement, which is still operating today to benefit all New Yorkers, opened one of New York City’s earliest playgrounds and paid the salary for the first public school nurse. Her focus was on solving the underlying issues rather than just addressing symptoms, applying three principles: research, residence, and reform. Wald’s vision created the Visiting Nurses and the NAACP.

Progress is Slow and Steady

Understanding history allows us to learn from our experiences and gain perspective. Kaplan pointed out that everything has both a positive and a negative side. Industrialization created wealth, and assembly lines mass-produced items, but at the same time, many insist that industrialization dehumanized workers by giving them repetitive mindless tasks. While child labor laws protected minors, the factories that had relied on children for cheap labor–and their families that had depended on their salaries–needed to adjust to survive.

Kaplan’s ability to tie the past to the present sparked awareness of how far we have come. His is a cautionary tale, a reminder that creating lasting change requires a slow, steady process. We may get caught up in the moment, awed by our impact, yet it is only by looking back can that we can fully recognize progress and, hopefully, note where we have gone wrong.

Kaplan’s books and zoom talks are always stimulating and provoke thought and conversation.

***

Two Sues on the Aisle bases its ratings on how many challahs (1-5) it pays to buy (rather than make) in order to see the play, show, film, or exhibit being reviewed.

Lower East Side Jewish Conservancy (LESJC) Progressive Era book talk received a 3 challah rating