The Making of a President: Eisenhower—Great American? Yes; Great President? New Play Says, Yes again

By Sue Weston and Susan Rosenbluth – Two Sues On The Aisle

In 1952 and 1956, General Dwight D. Eisenhower ran successfully as a Republican for President. In both elections, the vast majority of American Jews not only voted for his opponent, Democrat Adlai Stevenson but, for the most part, participated in the vilification and ridicule of the 34th President as a reader of Western novels who took naps in the afternoon and played golf–as opposed to Stevenson, who enjoyed a reputation as “an intellectual.”

According to a new one-man play, now being shown at the Theatre of St. Clements in Manhattan, Jews weren’t the only ones wrongly underwhelmed by Eisenhower. Eisenhower: This Piece of Ground, written by Richard Hellesen, opens in 1961, when the recently retired President was writing his memoirs from his farm in Gettysburg, PA.

Played by the superb John Rubinstein, Eisenhower isn’t sure it’s worth the effort, not after 75 historians have just decided, on the pages of the New York Times Magazine section, that while Lincoln was the “best” President the United States ever elected, Mr. Eisenhower fell into the at-best-mediocre category of 22nd out of 34. The Times called him “a great American–not a great President.” American Jews might not have gone that far.

Adding insult to injury, his successor was the wildly popular John F. Kennedy, who had defeated Eisenhower’s two-time Vice-President, Richard Nixon.

An Intimate Look

The play provides an intimate look into Eisenhower’s post-White House life in which he and his wife, Mamie (she makes an “appearance” only when she calls him on the phone), lived like normal people–albeit ones who had enjoyed a front-row seat to history.

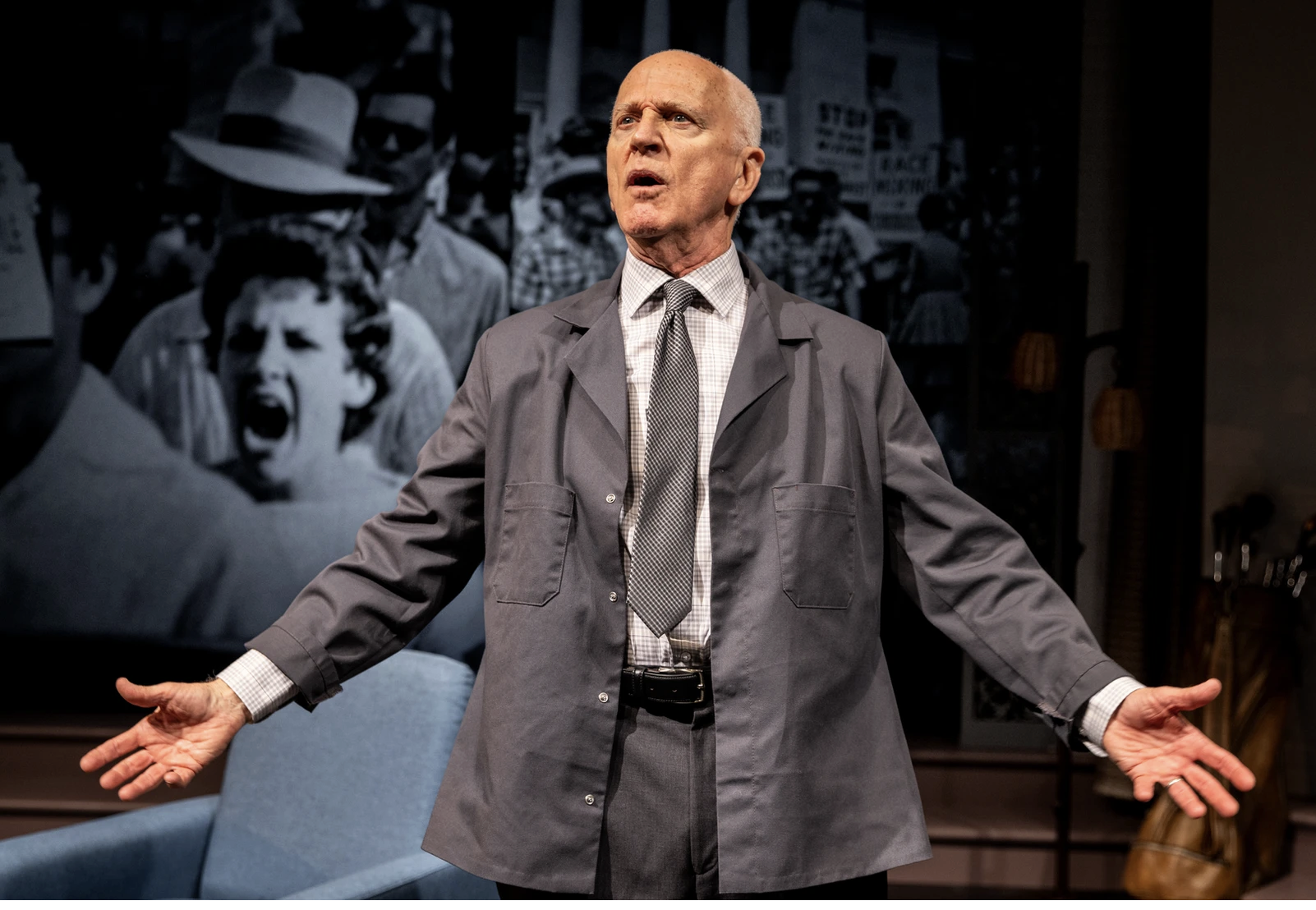

There is no question the show’s success is largely due to the skill of the perfectly cast Mr. Rubinstein, who breathes life into Eisenhower, duplicating with amazing verisimilitude his accent and mannerisms. He captures the essence of the President who defined the 1950s, portraying him as a powerful, thoughtful leader whose actions shaped America for decades.

Mr. Rubinstein’s portrayal feels authentic. He raises his voice at the outrage of being judged, repeating his mantra: “We have to keep choosing the harder right instead of the easier wrong.”

The result is a believable presentation of a man who had led his country to victory over the Nazis barely seven years before running for office and who, after eight years as President, faced the daunting task of sharing introspection, mixed with frustration, that his impact on history was being overlooked—at least by some 75 historians.

Liberator of the Camps

Sitting through Eisenhower’s recollection of his war years is enough to prompt us to wonder why more Jewish Americans didn’t vote for him. He was personally present at the Buchenwald sub-camp, Ohrdruf, the first Nazi camp to be liberated by US forces. Eisenhower and General George Patton toured the site, led by a prisoner who pointed out the corpses scattered around the camp, and left where they were killed prior to the camp’s evacuation. They discovered the charred remains of prisoners as well as evidence of torture, proof of the SS’s attempts to cover their crimes.

In a shed, a pile of roughly 30 emaciated bodies were discovered, they had been sprinkled with lime in an attempt to cover the smell. Patton, no stranger to the violence of the war, refused to enter the shed, the odor was too overwhelming. Eisenhower not only went into the shed but then rounded up citizens from the town outside the camp, forced them to see what was there, and then compelled them to bury the dead–all captured by the cameras Eisenhower insisted had to memorialize the event. This became the standard procedure for all camps liberated by US troops.

In the play, Eisenhower says he brought in the cameras because he knew, in years to come, people might say this couldn’t have happened. He wanted the truth to be recorded.

Left undiscussed in the play was Eisenhower’s behavior in 1956 when he faced his greatest foreign policy challenge: the Suez Canal crisis in which Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser seized control of the canal and was then attacked by Great Britain, France, and Israel. The US had promised to stand with the Western powers and the Jewish state, but, under the influence of anti-Israel Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, the ailing Eisenhower (he had suffered a heart attack in 1955 and needed surgery for an intestinal blockage in 1956) reneged.

Timely Lessons

These issues aside, Eisenhower: This Piece of Ground is a biographical drama filled with timely lessons delivered by a humble and not overly charismatic leader who firmly believed he was prioritizing the needs of his country. His focus, he tells us, was to provide behavioral correction to avoid the reoccurrence of poor behaviors, even if he wouldn’t be in office when they’d be attempted. A President’s tenure, he says, requires a hand-off to the next administration, hoping they can bring these initiatives to completion.

Whether Eisenhower is structuring a rebuttal or preparing his memoirs, the focus offers an opportunity to review his past, beginning with his youth. He shares his mother’s disappointment with his decision to attend West Point. The man responsible for the success on D-Day never sought a military career or aspired to be President, but West Point offered him a no-cost education, and afterward, politics became an obligation.

A recurring theme of the play is Eisenhower’s perception that he made the best available choices. The one he was most proud of was the decision to marry Mamie, and he suggests that had the New York Times ranked first ladies, she would have fared far better than he did.

A Man of His Time

The show meanders across Eisenhower’s achievements, regrets, and personal tragedies, including the death of his father and a child. He makes clear he took responsibility for the troops under his command without regret.

After the war–but before running for President–he served as president of Columbia University. In 1950, he took a leave of absence from his position at the school to become the first supreme commander of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). He retired from the service–but not from Columbia–to run for President.

His self-exploration offers context of his time in power, which, perforce, has to include discussions of McCarthyism, the Cold War, and the fledgling Civil Rights movement. Many of his reminiscences are punctuated by pictures projected on the set’s bay window, such as footage of his sending federal troops to Little Rock, Arkansas, to protect African-American students from angry mobs.

His accomplishments at the White House range from the creation of the Interstate Highway System to greenlighting NASA.

The Eisenhower presented in the play sees his achievements as the fulfillment of opportunities with which he was presented and could not refuse. He was motivated, he says, by the need to serve not driven by ego or dreams of power.

Realistic Setting

Mr. Hellesen’s incorporation of words taken from Eisenhower’s memoirs, speeches, and letters is impressive. The authenticity and realism are magnified by a period-appropriate setting achieved by Michael Deegan, who expertly designed a backdrop without which the play would depend on narrative without visuals.

The play takes the audience into Mr. Eisenhower’s study complete with a black rotary phone; a big, bulky tape recorder; and a massive bay window overlooking the farm and his putting green. It ends with the indication of a thunderstorm, darkening the skies of Gettysburg. It could be a metaphor for the tempest brewing in the turbulent 1960s just ahead.

Thanks to Mr. Rubinstein’s performance, the two-hour play, including a ten-minute intermission, is often riveting, and the message it brings is as relevant today as it was in 1960: politics has the ability to connect or divide a country. Eisenhower sought alignment between his beliefs and his actions, and, as a former military man, he wanted, at all costs, to avoid war and create détente whenever possible.

U2 Incident

One of the play’s most poignant moments is his discussion of the downed U2 spy plane in 1960, shortly before he left office. His choice to lie about the incident makes him wonder what could have been accomplished had he told the truth. “Never be content with half-truth when the whole truth can be ours” is another Eisenhower mantra.

“Sometimes,” he says, “it feels like Democracy is going to have a helluva time persevering, but this piece of ground that we all share—if we’re going to leave our young people something better—then we just can’t be complacent. It’s going to have to be the nation that we’re serving and not just ourselves.” Lines like that result in people leaving the theater a bit smarter, more knowledgeable, and maybe awed by Eisenhower’s impact.

Eisenhower: This Piece of Ground is an interpretation of history, a fireside chat if you will, reminding us that political affiliations should be binary and there is sometimes a role for moderation.

Tellingly, the New York Times ranking, taken shortly after Eisenhower left office, has changed, rising dramatically over the years, a measure either of the underestimation of his accomplishments at the time or the grandeur they assumed in light of later, much worse Presidents.

*******

Two Sues on the Aisle bases its ratings on how many challahs (1-5) it pays to buy (rather than make) in order to see the play, show, film, book, or exhibit being reviewed.

Returns to the Theatre at St. Clements (423 W. 46th Street, NYC) for a limited run from October 2 through October 27. Tickets are now on sale at OvationTix.com.

Eisenhower: This Piece of Ground received four Challahs