Immersive History – Discover Tut

By Sue Weston and Susan Rosenbluth – Two Sues On The Aisle

If immortality means being remembered by future generations, then King Tut, the boy pharaoh whose fame and attraction can still garner headlines almost 3500 years after he was born, might be the poster child for timeless eternal life.

By the time he assumed the throne—about 1331 BCE—the Israelites, according to Jewish tradition, had been in Egypt for hundreds of years. Many of the glorious artifacts found inside King Tut’s tomb, treasures of the ancient world, may have been fashioned by Jewish slave labor.

According to the reckoning by most historians, King Tut, the antepenultimate pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt, died about eight years before Ramses I, the first pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty, took the throne. Less than a century later, Ramses II, the pharaoh of the Exodus, was Egypt’s ruler.

All of this brings a particular interest to National Geographic’s immersive experience, “Beyond King Tut,” a multi-media exhibit designed to transform history into an interactive journey. Bringing new relevance to relics of antiquity, the showcase allows visitors to become part of the expedition that discovered the tomb, bringing a deeper understanding of the boy king and the mythology of the Egyptian journey to the afterlife—the ambiance in which the Israelite slaves lived so many centuries ago.

Ancient Turmoil

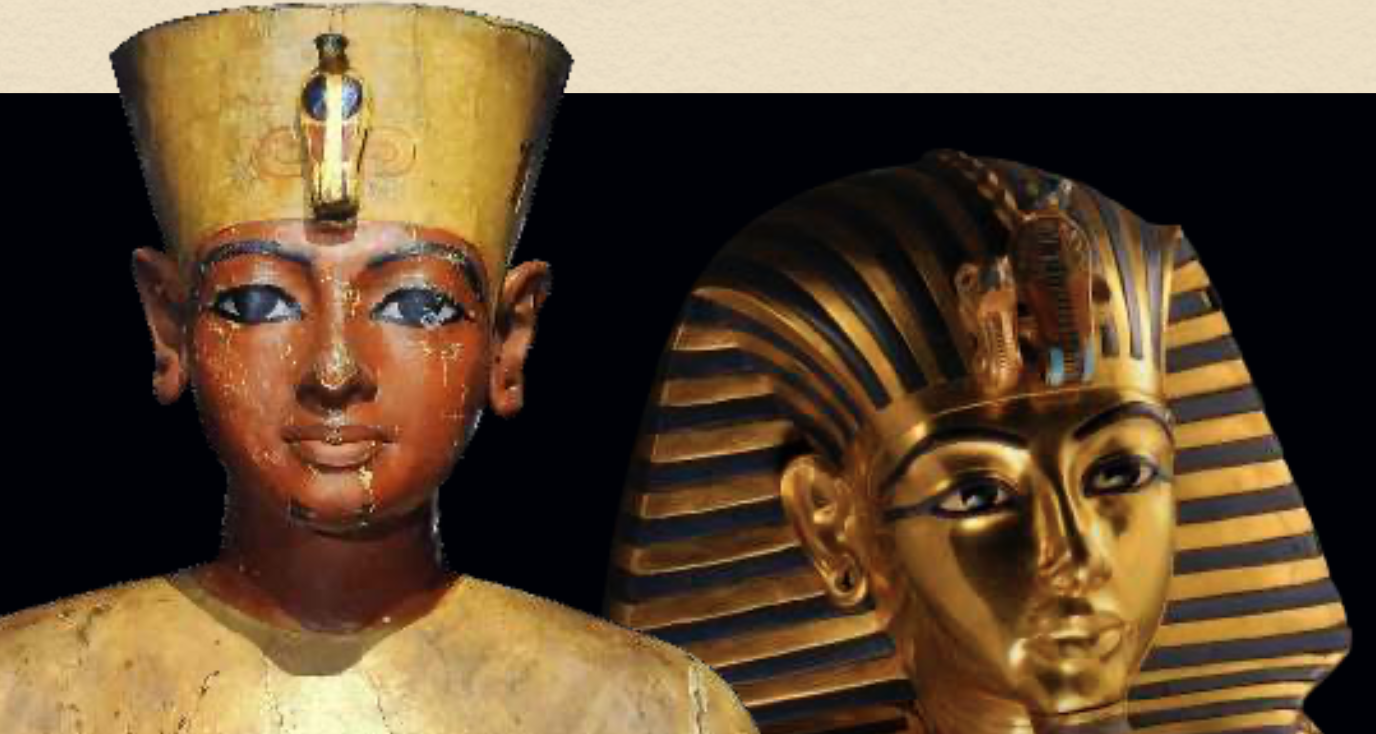

Tutankhamun (born Tutankhaten about 1341 BCE) was known only to Egyptologists when, in 1922, his nearly-intact tomb was discovered by British archaeologist Howard Carter in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings. Dubbed King Tut, he was only about 18 when he died in 1323 BCE amidst religious and political turmoil that can still excite the imagination.

His father assumed the throne under his birth name, Amenhotep (“Peace of Amun,” the king of the Egyptian gods), but around the fifth year of his reign as pharaoh, he changed it to Akhenaton (“Successful for the god Aten,” symbolized by a solar disk with rays ending in small human hands). The new name represented his new belief, one that challenged Egypt’s longstanding priestly classes with a visionary religion: monotheism. Temples devoted to the old gods were closed, and statues, including those of Amun, were destroyed.

When his son reached the throne at the age of about nine, he undoubtedly fell under the influence of counselors devoted to the old faith, and he reversed his father’s efforts to change Egypt’s theology. The gods and goddesses his father had dismissed were restored. Thus, Tutankhaten (“living image of Aten”) became Tutankamun (“living image of Amun”).

His death seems to have been unexpected as evidenced by the rushed construction of his tomb, leading to speculation that the relatively small mausoleum might have been prepared for someone else. He left no heirs, and his reign was passed on to his chief advisor, Ay, the last of the Eighteenth Dynasty’s pharaohs.

Birth of Monotheism

For Jews, the intrigue behind the pharaonic chronology lies beyond history and edges into the realm of spirituality. Some scholars—virtually all of them alienated from the Judeo-Christian tradition—have speculated that Jewish monotheism arose from what can be called Akhenaton’s Aten-ism. Since there are virtually no similarities between either the customs or the fealty owed to Aten and the faith tradition of the Jews for G-d, that hypothesis has been almost universally debunked.

There is, however, another theory: Is it possible the Israelites influenced the religious beliefs of Amenhotep? By Amenhotep’s time, Jews, who had arrived in Egypt with a well-delineated tradition of faith in one G-d, had been living under the pharaohs for some 300 years. Could Amenhotep have been sufficiently taken by what he saw of their monotheism to prompt him to adopt the worship of a single god—and, in so doing, almost change Egyptian history?

Archeological Journey

Don’t look for answers to such questions in “Beyond King Tut,” but it is certainly food for thought as the life of the boy king, the country and times in which he lived, and the faith he practiced are explored.

The journey begins by entering a tent as members of the archeological mission led by Mr. Carter. Sitting on benches, participants are privy to a briefing—a video introduction—that provides background information and historical perspective. Afterward, the back of the tent slides open, revealing weathered walls, each displaying flickering images of news clippings with information about the tomb and the legend of King Tut.

Dimly lit catacombs approximate the experience of unearthing and exploring the tomb, each twist revealing glimpses of hidden spaces connecting the antechamber, annex, and treasury within the burial chamber.

Treasures and Their Meanings

For more than 3,000 years, the tomb and its more than 5,400 items—everything the boy king might need for, first, his journey to the world-to-come and, then, his eternal life there—had lain undisturbed, encased in walls of gold, protected amid the rubble of larger tombs.

The maze leads to a display of the burial chamber with a replica of a sarcophagus in the center, and the contrasts are striking: the darkness of the tunnel followed by the brightness of the burial chamber. Visitors can only imagine the astonishment of Carter and his party.

Juxtaposing the quiet of the exhibit’s scenic representation is an audio/visual presentation running on a continuous loop, explaining Tut’s transition to the netherworld. Imagery projected on the walls includes twelve baboons, guides for the king’s—and all his predecessors’—transition, one for each hour of the predestined assent.

An animation depicts the three protective layers within the sarcophagus, and a video describes Egyptian religious rituals, such as the “opening of the mouth” to allow the deceased to eat and drink again, an essential process that, according to their theology, reanimated the ka, or life force.

Leaving this chamber, visitors encounter a series of galleries devoted to Ancient Egyptian practices, including the embalming process and legends of deities. A large space shows off replicas of artifacts Tut would not only have recognized but might well have enjoyed, such as a child’s game and an ornate throne, all of which are intended to be touched and photographed.

The walls are lined with photographs and written explanations of Tut’s family tree.

Traveling with Tut

The exhibit is impressive, but it is only the prequel to the immersive experience—an introduction to Egypt and an excursion to its ancient concept of the afterlife—that lies ahead.

A pageantry of colors and imagery subsumes the space that is lined with benches, all facing the replica of a boat in its center. That boat, manned by Anubis, the Egyptian god of the dead, allows us to watch Tut move through a domain filled with terrible beasts he must subdue in order to reach the realm of the Duat (land of the gods).

After winning his battle with a giant serpent, Tut earns an audience with the gods in the Hall of Osiris where he will be judged. To gain eternal life, his soul must be lighter than a feather from Ma’at, the goddess of truth, justice, balance, and, most importantly, order. Those who fail are doomed to be eaten by a waiting beast, Ammit. Fortunately, Tut passes the test.

The immersive experience also provides information—considerably less stirring—about modern-day Egypt.

Using Modern Technology

Combining research, intrigue, and investigation, “Beyond Tut” shows how modern technology allows scientists to dig deeper into ancient history, including, of course, the legacy of Tut.

Computerized tomography (CT) scans of Tut’s remains show that he suffered from deformities, including a cleft palate, a curved spine, and a clubbed foot—which probably explains why 130 walking canes were found in his tomb.

At the time of his death, Tut had a badly broken leg that may have become infected—and he had malaria.

Virtual Reality

The exhibit ends with a seven-minute virtual reality experience. Using a VR headset, visitors re-enter the tomb, this time standing right in the middle of the treasures. It offers the ability to learn more about the tomb’s contents from a very different, in many ways, more intimate, perspective. The chariot the teenaged Tut enjoyed for racing (and may have been the cause of his fatal leg injury) stands alongside his canes and other provisions tucked away to sustain him on his journey to the afterlife.

He has detailed carved figures, Ushabtis, among his grave goods, placed there to act as servants who can be summoned to life by a spell to attend to his needs.

It’s easy to understand why Carter—and all those who followed him over the years—have been so surprised by the sheer number of possessions packed into the tomb, to say nothing of the information scientists have been able to extract from them. Mold on the walls means the paint was not yet dry when the burial chamber was sealed, lending credence to the theory that the tomb had been prepared rapidly.

“Beyond King Tut” uses the power of immersive storytelling to provide a splendid historical experience. Information is presented in a variety of ways, allowing visitors to find the style most appealing. Each segment reinforces the details and provides a sense of familiarity with the discovery of Tut’s tomb and Ancient Egyptian mythology.

Bringing History to Life without Traveling

Created by Paquin Entertainment Group, in association with Immersive, “Beyond King Tut” is among the experiences ushering in a new era of virtual museums. While nothing will ever replace seeing art and the antiquities up close, live, and personal, immersive experiences allow patrons to participate in what is, perhaps, the next best thing: the opportunity to wander amid the imagery, soaking in information, rather than traveling.

The increasing number of immersive experiences popping up in New York and elsewhere may represent the next generation of art and science combining to gather information, offering experiences that bring history to life.

“Beyond King Tut” should be seen by adults and children whenever possible.

*****

Two Sues on the Aisle bases its ratings on how many challahs (1-5) it pays to buy (rather than make) in order to see the play, show, film, or exhibit being reviewed.

Beyond King Tut Received a 5 Challah rating