Holocaust on the Stage

By Sue Weston and Susie Rosenbluth, Two Sues on the Aisle

Call it karma; call it coincidence, but for some reason, it seems like there are more productions about the Holocaust on and off Broadway than ever before.

It can’t be attributed to Hamas’ October 7 attack on Israel and the horrific uptick in antisemitism in its wake. Most of these plays and musicals were in the works for months—sometimes years—before October 2023. But they are here, and even though they deal with events that occurred more than 80 years ago, they feel frighteningly relevant. The stage provides a medium to educate and personalize all experiences, and when it turns its eyes on Jewish history, the gut punch can serve as a reminder of the power of hatred to destroy and the strength required to survive.

Several amazing productions, all based on true stories, have done just that, and their recurring themes remain as true today as they were decades ago: hatred defies logic; when people threaten to kill you, believe that they mean it; and recognize that persecution often begins with small groups. No one is immune.

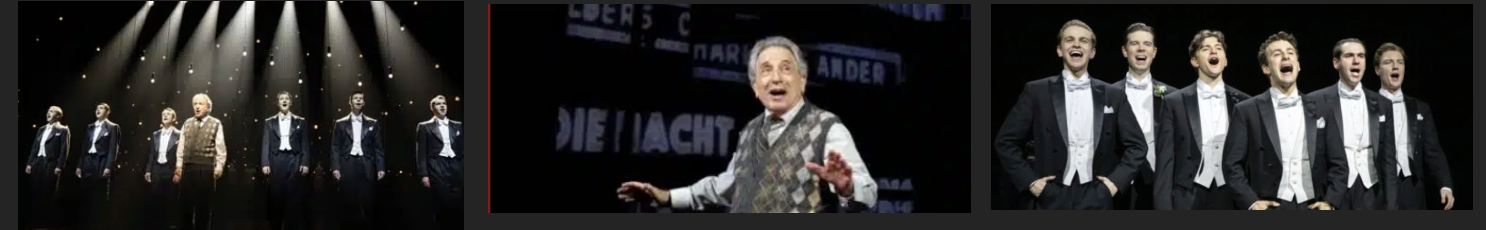

Harmony

Harmony, which is playing on Broadway, is a good place to start. The story of a handful of very talented musicians most of the world has forgotten, this tale of one of the first successful boy bands, with music by Barry Manilow and lyrics by Marc Sussman, is on its way to becoming a classic. Like Cabaret, it is a reminder of the power of senseless hatred that all but erased the success of six young men—three Jews, three Gentiles (one of whom married a Jew)—who became internationally known from 1928 to 1934 as The Comedian Harmonists. They sold millions of records, starred in some 21 major European motion pictures, and played in some of the biggest theaters around the world until 1935, when the Nazis insisted on censoring their material and, eventually, forbade them from performing altogether, essentially erasing them.

The show is presented as a retrospective from the point of view of the last surviving member of the group. Known in the show as “Rabbi,” Joseph Roman Cycowski (played as a young man by Danny Kornfeld and as a much older survivor by Chip Zien) was trained in Poland as a cantor and had his sights set on a career as an opera singer in Germany before he joined the Comedian Harmonists. One of the regrets he expresses in Harmony revolves around an action that seems more for dramatic effect than reality would call for—the “missed opportunity” to assassinate Hitler when the Fuehrer was riding on the same train as the young musicians.

The Second Act was, in its own way, more crushing. In December 1933, months after the Reichstag fire had allowed then-Chancellor Hitler to suspend most civil liberties in Germany, the Comedian Harmonists were playing Carnegie Hall to great acclaim. They were at the height of their career and could have remained in America and the Free World, performing with the likes of Josephine Baker (Allison Semmes) in the Ziegfeld Follies. But by consensus, the group decided to ignore very serious warnings—including one from Albert Einstein—not to return to Germany.

Their inability to foresee how the hatred subsuming Germany would cost them their careers and the music is tragic—and all too understandable. The young men believed they were too talented and popular to be stopped by the Nazis. They were, of course, wrong.

Bridging Ethnic Divides

When they first formed the group, the idealistic young men had intentions of showcasing their talent while bridging ethnic divides. This naïve optimism prompts “Rabbi” to marry non-Jewish Mary (the incredible Sierra Boggress), whose conversion to Judaism is undoubtedly sincere, as he sings “Tell me how we live in a world that is crumbling away and be as happy as we are today.” At the same time, “Chopin,” a non-Jewish, classically trained musical arranger (Blake Roman), marries Ruth, a rabble-rousing, passionate Jewish Bolshevik (Julie Benko). In the show, Ruth is the only member of the group whose death is mourned. From 1933-1938, the real Erwin “Chopin” Bootz was married to a Jewish woman—the first of his three wives.

All Survived

The show implies that at least some of the members of the group died in the Holocaust. That didn’t happen. After the group disbanded, the three Jewish members—“Rabbi” Cycowski, Harry Frommerman (the one who originally came up with the idea of a group of men singing in perfectly blended harmony, played by Zal Owen), and Erich Abraham Collin (Eric Peters)—fled first to Vienna, where they formed their own group and played throughout the Soviet Union, South America, South Africa, and Australia, where they were offered citizenship. In 1940, they toured the United States and were unable to return to Australia. Their last concert was in Richmond. Ironically, after that 1940 tour, hostility in the US toward German entertainers made it impossible for them to get work.

The non-Jewish members of the original group banded together with three others in Germany and, for a short time, performed as Das Meistersextett—the Nazis had forbidden the use of English names.

Although all six of the original Comedian Harmonists survived the war, they never worked together again. In 1941, “Rabbi” learned his father had been murdered in the Lodz Ghetto, and he and his wife, Mary, moved to California, where he served as a cantor until he was well into his 90s. He died in 1998 at the age of 97.

Spectacular

The show is, in a word, spectacular. The collaboration between Messrs. Manilow and Sussman has resulted in songs that capture the era, ranging from sweet, romantic ballads, “This Is Our Time” and “In This World” to comedy shtick, “Your Son Is Becoming a Singer” and “How Can I Serve You, Madame?” Many of the performers in the Broadway production have been with the show for a while, and after seeing them in the smaller Off-Broadway space at The Museum of Jewish Heritage, where it was mounted by The National Yiddish Theatre Folksbiene, it was a pleasure watching them enthuse audiences on the big stage.

During the performance we attended, there was no mention of the current spate of antisemitism playing out on the streets of New York not far from the Ethel Barrymore Theater, but when, as part of the show, a cry came to stop the Comedian Harmonists’ performance—“Save Germany from the Jews”—a gasp could be heard. It hit too close to home.

Harmony encapsulates the essence of the joy of collaboration when people from different backgrounds create art and teaches us, once again, how fragile and temporary happiness can be.

***

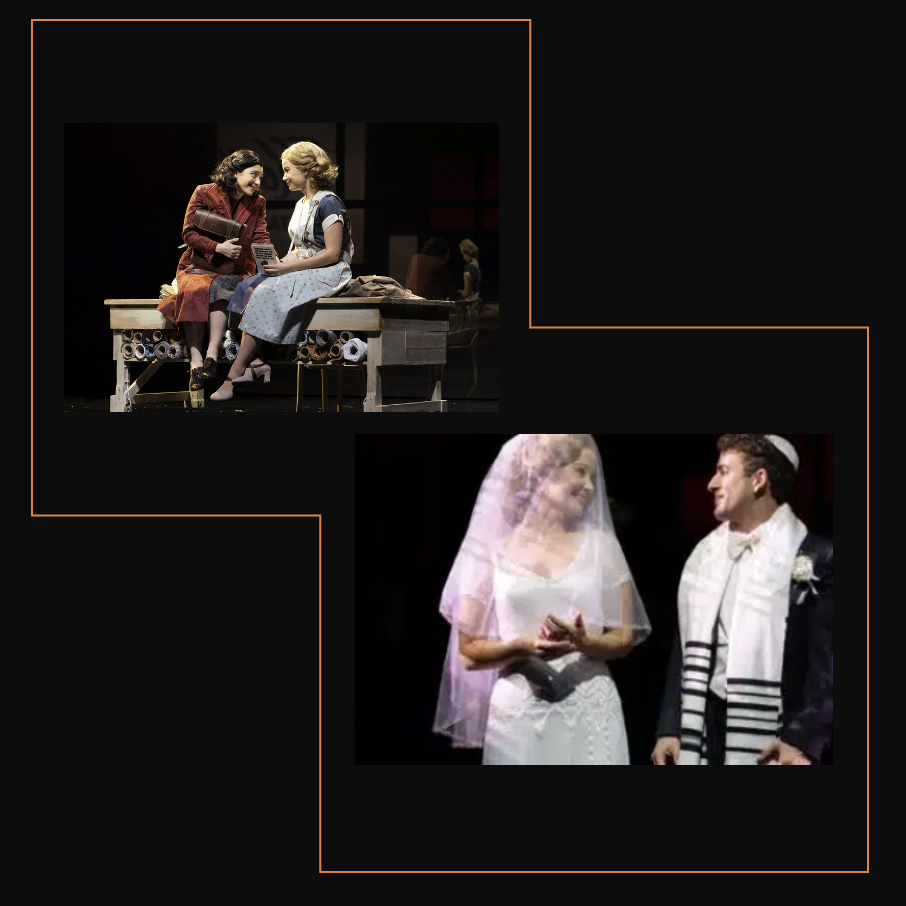

King of the Jews, which played last fall at the very tiny HERE Arts Center, 145 Sixth Avenue in Manhattan, was adapted by Leslie Epstein from his 1978 novel. A darkly comic piece of “historical fiction” that explores the intricacies of human nature in the face of the impossible.

It’s based on the true story of Chaim Rumkowski, an insurance agent in Łódź, Poland, who, from 1925 to 1939, also served as head of a Jewish orphanage. When the German occupiers ordered the creation of Jewish Councils, known as the Judenrat, to act as the bridge between the Nazis and the prisoner population of the ghettos, Rumkowski was appointed Judenältester (“Chief Elder of the Jews”). He reported directly to the Nazi ghetto administration, and when the rabbinate was dissolved, he even performed weddings. He came up with the idea of using his name—and face—for the ghetto’s money (the Rumki or Chaimki) and postage stamps, which led to his sarcastic nickname “King Chaim.”

Holocaust-Era Nightclub

In Mr. Epstein’s theatrical adaptation, directed by Alexandra Aron, the audience walks into the Astoria Café, a Jewish-owned nightclub in 1939, and is seated at tables adjoining those occupied by members of the cast. Musicians, all of them wearing the telltale yellow stars, warm up on the small stage.

The mood, however, is congenial as locals, including the café owner (Richard Topol) and his singer-wife (Rachel Botchan), a bartender, a visiting doctor, and at least two rabbis, who are arguing about who owes whom damages, strive to keep the place open even as curfew is nearing. A comedian onstage tells jokes about someone named Horowitz, a stand-in for another fellow whose name also begins with “H.”

Out of nowhere, a young boy falls through a window into the café with the Nazis in hot pursuit. The Nazi administrator of the town, Wohltat (Daniel Oreskes). enters, his manners polite, his smile bright. “Ah, my friends. It’s a shame to intrude on your evening.” He’s looking for the boy, but he wants something else: the establishment of the Judenrat. “Only the seed of Abraham knows how to work among their own people.”

“Choose”

The choice thrust upon the Jews with threats delivered in the guise of thinly gilded flattery is simple: choose someone to lead the council, to make the decisions, because only by serving on the Judenrat can the Jews protect themselves and their families.

Thus, this nondescript group becomes the council, and the Astoria Cafe the epicenter of the Lodz world, the place where Nazi-sanctioned policies are executed. The first order of business is to choose a president, an elder whose word will be law. “He will ride through our streets in a motor car, His face will be on posters placed on every wall.”

The Nazi administrator tells them to “pick your most intelligent, your most resourceful, your most courageous leader.”

Throughout this discourse, there are reassurances: all will be fine eventually, and the Jews will be sent to a farm to milk cows, plow fields, and ultimately be relocated to Madagascar. The Jews in the café know these are lies, that Jews are being sent to death camps or being killed in the woods. The boy, whom they are hiding, describes witnessing his family killed and gassed in a bus.

Attempts to Rationalize the Irrational

Act Two opens 18 months later as the Judenrat confronts the kind of moral dilemma no one should have to face: who among their fellow Jews is to live and who is to die.

Using grand language, they try to rationalize: that maybe by sacrificing a few, we can save the majority. Maybe we can get the Germans to reduce the number of names on the quota. This might temporarily save a few lives. There is reason in this madness, they tell themselves. Maybe Russia will arrive in time to save the Jews. They know it won’t happen, but by grasping at flawed logic, combined with enjoying their elevated status as members of the Judenrat, they seek momentary solace.

Sitting alongside them in the café, the audience becomes part of their desperation, recognizing the need for self-preservation in the absence of a better solution. Ultimately, they make the only moral choice possible—one the real Rumkowski didn’t. He will always be remembered for handing over thousands of Jews to the Nazis, culminating in his notorious 1942 “Give Me Your Children” speech, in which he exhorted the Jews of the ghetto to turn over their children, ten years old and younger, as well as the elderly over 65, to fulfill the Germans’ death quota.

By all accounts, Rumkowski was a despicable tyrant who was not above beating Jews who disobeyed him, in 1944, Rumkowski and his family were herded onto the last transport to Auschwitz, where he was beaten to death either by the Jews of Lodz who had preceded him there or at their behest by members of the Sonderkommando, Jews whom the Nazis forced to torture and kill Jewish prisoners.

***

Among the many Holocaust memoirs, the one receiving the most attention this season is Wladyslaw Szpillman’s The Pianist. Last fall, a play with music based on the autobiography of Mr. Szpillman, a Polish-Jewish pianist and classical composer, was presented at the George Street Theater in New Brunswick. Directed and adapted by Emily Mann, it is the harrowing account of the annihilation of Jews during World War II and Mr. Szpillman’s remarkable survival through the transcendent power of music.

His autobiography, The Death of a City (originally Śmierć miasta) was written in 1945 and further elaborated on by Jerzy Waldorff a few years later.

This month, from January 26 through February 1, a new 4K restoration of Roman Polanski’s 2002 Academy Award-winning film, The Pianist, will run at Manhattan’s Film Forum, at 209 West Houston Street, in Manhattan.

The film stars Adrien Brody, in the Oscar-winning performance as Mr. Szpilman, and Thomas Kretschmann, as the music-loving Wehrmacht officer, Wilm Hosenfeld, who detested Nazi policies.

Deterioration of a City and the Lives in It

The story begins with a depiction of the deterioration of Warsaw from the cosmopolitan center where families of artists and academicians, such as the Szpilmans, could thrive to the war-torn hulk that remained after the war.

In 1939, all the Szpilmans, except for Wladyslaw, were deported and killed. Alone in the ghetto, he survives as a laborer and smuggler, hiding and transporting forbidden weapons for the Jewish resistance. With the help of friends, he manages to hide from the Nazis while keeping his music alive in his heart and mind by composing on an imaginary piano.

A celebrity before the war and a featured soloist on Polskie Radio, Mr. Szpilman was able to continue his career in Poland and abroad after 1945.

Multi-Talented Jewish Actor

Perhaps Ms. Mann’s most dramatic effect had nothing to do with the multi-media sets and other aspects of modern theatrical wizardry. During most of the play, the actors on stage portraying the Szpilman family musicians pantomimed the act of making music, moving their fingers and hands in time to acoustically supplied sound. But suddenly, when the young, half-starved, desperately frightened Wladyslaw, who hasn’t touched a real piano in years, is confronted by a magnificent instrument in his newest hiding place, he sits on the bench and really plays.

It’s an act of lavish bravura that showcases the artistry of the young actor playing the part of the protagonist. In this, Ms. Mann really lucked out. In his American stage debut, the Russian-German-Israeli Jewish actor, Daniel Donskoy, knocked it out of the ballpark. His ability to encompass the pathos of the frighteningly lonely Szpilman and then play like the virtuoso he was, are the heart of this production.

Asked about his expertise as a pianist, Mr. Donskoy, 33, paid tribute to his grandmother, his first teacher.

“Music has been the language I could utilize throughout the different countries I grew up in,” he said.

Donskoy’s Many Roles

Born in Russia, he grew up in Berlin until he was 13 when his mother married an Israeli and he finished high school in the Jewish state. From there, Mr. Donskoy relocated to London, where he studied biology and acting. He played Israeli gangster Danny Dahan in the HBO series Strike Back, and in 2020, he played Princess Diana’s lover, James Hewitt, in the Netflix series The Crown. Earlier this year, he played the part of a Nazi soldier in the Disney Plus series, A Small Light, the story of how Miep Gies hid her boss, Otto Frank, and his family, including his daughter, Anna, from the Nazis in Amsterdam during the Holocaust.

He now divides his time between the UK and Germany, where he recently hosted two seasons of a late-night talk show, Freitagnacht Jews, which translates to Friday Night Jews. He says it offered Jews a platform to discuss their identity.

Tenacity of the Human Spirit

For Ms. Mann, The Pianist was “the most important story I’ve been entrusted with as a theater maker.”

“Not only is it a stunning story about the tenacity of the human spirit and the power of art, but it is also deeply personal. Since I was a child, I’ve been haunted by my mother’s family, murdered in occupied Poland during the Holocaust. When I went to Warsaw to research The Pianist, I visited the Jewish cemetery and placed a stone on my great-grandmother’s grave. At that moment, I realized I, too, was a Warsaw Jew, and I had to tell this story. Seeing fascism on the rise again both in the United States and around the world gives even greater urgency to this play. We must bring to powerful life the call to action ‘never again.’”

On a beautiful morning last fall, scores of eighth-grade students from Jersey City’s public schools came to see the play, which had been integrated into their curriculum as part of their studies about the Holocaust. During the talk-back following the performance, some kids asked if learning “all those lines” was difficult; another wanted to know how best to study to become an actor. Only one question was asked about the relevance and impact on the actors of the October 7th attack on Israel.

Mr. Donskoy answered that playing the part of Wladyslaw Szpillman just weeks after the October 7 Hamas attacks “brought home the fragility of the Jewish sense of security.”

“I have friends and family still running to shelters whenever a siren screams its warning about incoming missiles. How many Jewish-Israeli children are missing their piano lessons because they’re sitting in safe rooms?” he said.

It caused us to wonder if the students and faculty were “processing” the events they’d just witnessed playing out on the stage, or has the coarseness of the fabric of life around them left them desensitized and emotionally numb.

Recreating History

Theater has the ability to recreate history, bridging time to forge a personal connection and provide perspective. Happy endings make for satisfying stories but they don’t answer all the questions productions about the Holocaust leaving us asking. Like in the tales of Jewish holidays—we were outnumbered; our enemies tried to destroy us, and with the help of G-d, we survived—we as a people outlived the 20th-century foes who wanted to annihilate us, but, as these plays remind us, innocent people died, and families were left broken.

As October 7th taught us again, the same behavior continues, seemingly unchecked.

In this, theater can also be a warning and a call to action, a demand not to be lulled into a stupor of acceptance in which we—like the characters in these stories—do not feel the threat until it is too late.

Never again!