Spoleto USA: Performing Arts Festival in a Magical City with a Distinctly Jewish History

Spoleto USA: Performing Arts Festival in a Magical City with a Distinctly Jewish History

Imagine a magnificently charming city, repeatedly recognized as a top tourist must-visit in the United States, whose cobblestone streets weave between pastel-colored antebellum residences and numerous historic sites, including many of specific Jewish interest. Now imagine this magical city swathed for 17 days in a plethora of musical events, theatrical and dance performances, artistic and craft exhibitions, and film screenings, and you have the Spoleto Festival in Charleston, South Carolina.

The Festival, which, this past spring, celebrated its 40th anniversary, is now recognized as one of the world’s major celebrations of performing and visual arts. Next year’s Festival will run from May 26 through June 11, and while the concerts and events have not yet been announced, it’s not too early to begin thinking about a Spoleto Festival vacation in Charleston.

The Festival in Charleston was founded in 1977 by the late Italian-American composer Gian Carlo Menotti, who, almost 20 years earlier, started the original “Festival of Two Worlds,” in Spoleto, Italy, and wanted to initiate a new one in America. In Charleston, Mr. Menotti found a perfect fit. Small and intimate so the entire city and its wealth of theaters and venues can be infused by the festival, Charleston is also sufficiently cosmopolitan to provide an enthusiastic audience and robust infrastructure.

“Porgy and Bess”

George and Ira Gershwin, who, along with Dubose and Dorothy Heyward, created “Porgy and Bess.”

The centerpiece of the 2016 Festival was a forceful production of “Porgy and Bess,” by Jewish composer George Gershwin and book and lyrics by Dubose and Dorothy Heyward and the composer’s brother, Ira.

Written in 1934 in Charleston, where it is set, “Porgy” was first performed in New York in 1935, with an entire cast of classically trained African-American singers. Although the opera’s story concerns the African-American residents of Charleston’s then poverty-stricken yet culturally rich black ghetto, the choice to use African-American singers was, at the time, a daring—and unpopular—artistic choice.

According to the Spoleto Festival’s general director, Nigel Redden, there was a reason behind the decision to delay a Spoleto presentation of “Porgy” until this past year. “The decision to mount a production of ‘Porgy and Bess’ in Charleston seemed obvious, and Spoleto Festival USA has tried over the years to avoid the obvious,” he said.

The current production was not only a tribute to George Gershwin musically, but also to his exploration of Gullah culture, the West African tradition transported to the New World by African slaves and still vibrant in the 20th century. While writing “Porgy,” Mr. Gershwin spent time listening to the cadences of choirs in the Gullah communities in and around Charleston.

The relationship between Mr. Gershwin, “Porgy,” and the local African-American community was further explored in the lovely Charleston Museum (often called “America’s First Museum,” because it dates back to 1773) and the city’s newly reopened Gibbes Museum of Art. Both are worthy of a visit. The Charleston Museum’s “‘I Got Plenty O’ Nuttin’: George Gershwin’s Charleston” looks at the city as Mr. Gershwin did in the 1920s and ’30s.

A Jewish Theater

But Spoleto 2016 was about a lot more than “Porgy and Bess.” There was, for example, a production by Dublin’s Gate Theatre of “The Importance of Being Earnest,” Oscar Wilde’s delicious spoonful of verbal jousting and comedy of Victorian morals. Small wonder Mr. Wilde subtitled the piece, “A Trivial Comedy for Serious People.” In the hands of the Gate Theatre, this was an effervescent, thoroughly enjoyable revival of a classic.

The production was shown in Charleston’s historic Dock Street Theatre, the first structure in America built exclusively for theatrical performances. It opened in 1736, but the original structure was probably destroyed four years later by Charleston’s Great Fire of 1740. In 1809, the elaborate Planter’s Hotel was built on the site,

Like most of Charleston, the Planter’s Hotel fell into disrepair after the Southern loss of the Civil War. The site was eventually bought by Milton Pearlstine, whose family immigrated to the United States from Poland in the 1850s. In the 1880s, they settled in Charleston, and opened the I.M. Pearlstine and Sons grocery store, which became Pearlstine Distributors, Inc, one of the oldest and largest privately owned companies in South Carolina. The Pearlstines, prominent members of the local Jewish community, became known for civic and religious philanthropy.

In 1935, Mr. Pearlstine made the property available to the city of Charleston, and the Dock Street Theatre was constructed within the shell of the old dilapidated Planter’s Hotel.

Thanks to Mr. Pearlstine, the new Dock Street Theatre enjoyed a $350,000 renovation and opened in 1937. Modeled on 18th-century London playhouses by Jewish Charlestonian architect Albert Simons, the new theatre boasts magnificent woodwork and mantels found in the old hotel as well as in nearby decaying mansions.

In 2010, the theatre underwent its third major renovation, this time for $19 million. It is now a state-of-the-art venue, used throughout the year, but, especially, by the Spoleto Festival.

Jewish-Themed Chamber Music

This year, the Dock Street Theatre was home to one of Spoleto’s real serendipities, the Bank of America Chamber Music Concerts. Hosted by the irrepressibly delightful violinist Geoff Nuttall, these superb concerts featured Mr. Nuttall’s St. Lawrence String Quartet along with an impressive roster of outstanding guest musicians. They performed pieces from the classical repertoire along with modern music, familiar ensembles, and groupings that were unusual—and all wonderful. The twice-daily concerts were nothing short of bubbling musical champagne parties that audiences were privileged to enjoy.

Of specific Jewish interest was the Chamber Music Concert’s presentation of music by Osvaldo Golijov, who served as this year’s Spoleto USA composer-in-residence. Born in 1960 to Eastern European Jewish parents who had relocated to La Plata, Argentina, he studied first locally and then in Israel at the Jerusalem Rubin Academy. After further study in the US, Mr. Golijov began working closely with Mr. Nuttall’s St Lawrence String Quartet. In 2002, he and the Quartet celebrated their 10th anniversary of collaboration with a Grammy-nominated CD entitled “Yiddishbbuk.”

At Spoleto 2016, Mr. Golijov showed why he is so well regarded for his musical hybridity, combining the traditions of classical chamber music, Jewish liturgical and klezmer music, and just a hint of Latin American rhythms.

Tenebrae and Yiddish Lullaby

One of the concerts featured Mr. Golijov’s 2002 work, “Tenebrae,” which was written after the composer had spent time in Israel, witnessing the start of the Palestinian violence that became known as the Second Intifada. One week after leaving Israel, he took his son to the planetarium at the Museum of Natural History in New York, where they could see Earth “as a beautiful blue dot in space.”

After the concert, he explained that he wanted to write a piece “that could be listened to from different perspectives.”

“That is, if one chooses to listen to it ‘from afar,’ the music would probably offer a ‘beautiful’ surface, but, from a metaphorically closer distance, one could hear that, beneath that surface, the music is full of pain,” he said.

The title is taken from the French, meaning “dark hours,” during which the Lamentations of Jeremiah, from the Hebrew Bible, are recited in Church. François Couperin wrote a piece entitled “Leçons des Ténèbres,” in which each of the first five stanzas begins with the singing of a Hebrew letter, aleph through hey.

Mr. Golijov sees his “Tenebrae” as “the slow, quiet reading of an illuminated manuscript in which the appearances of the voice singing the letters of the Hebrew alphabet, from yud to nun, signal the beginning of new chapters, leading to the ending section, built around a single, repeated word: Jerusalem.”

Although Mr. Golijov wrote “Tenebrae,” for a soprano, at Spoleto 2016, it was performed by a countertenor, Anthony Roth Costanzo, clarinetist Todd Palmer, and the St Lawrence String Quartet.

A day later, the chamber music concert featured Mr. Golijov’s “Lullaby and Doina,” for flute, clarinet, two violins, viola, cello, double bass, and harpsichord. It starts with a set of variations on a Yiddish lullaby that Mr. Golijov composed for “The Man Who Cried” by British filmmaker Sally Potter, whose film explores the suffering of Europe’s Jews and Gypsies during the mid-20th century.

A New “Golem”

Other Spoleto performances held in the Dock Street Theatre included “La Double Coquette,” a re-imagining of Antoine Dauvergne’s rather silly 1753 French opera, “La Coquette Trompée,” into an absurd work by Gérard Pesson. It was the American premier of the piece.

Towards the middle of June, when the Spoleto Festival was winding down, 1927, a London-based performance company that specializes in combining live action and music with animation and film, presented “Golem.” Written, directed, and designed by 1927co-founders Suzanne Andrade and Paul Barritt, it is loosely based on the Jewish story of a creature fashioned of clay to work for the benefit of the Jewish community and all mankind. In this piece, the fable becomes a dystopian symbol seeking to explore who or what is in control of our modern technologies.

Jewish History

After spending time in Charleston, it is not surprising that so much of the Spoleto Festival is of specific Jewish interest. It is an echo of the city itself, in which Jewish history is not so much celebrated as it is integrated into the whole of Charleston’s story.

Janice Kahn, a longtime Charlestonian, is a founding member of the South Carolina Jewish Historic Society and the owner of Chai Y’All tours of the city. She stressed that because Jews have been in Charleston virtually since its beginning, they are part and parcel of everything that has happened in the city.

“When we go out on a tour, I discuss the Jewish sites as well as the general history of the city, so it’s two tours in one. You just can’t separate one from the other,” she said.

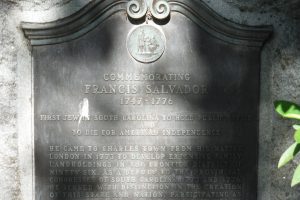

Francis Salvador

The plaque commemorating Francis Salvador, 1747-1776, recognizes that he was the first Jew in South Carolina to hold public office and to die for American independence. “Born an aristocrat, he became a democrat; an Englishman, he cast his lot with America; true to his ancient faith, he gave his life for new hopes of human liberty and understanding.”

For example, one of Charleston’s loveliest parks is located directly opposite City Hall. Called alternatively Washington Park (because a statue of the first President dominates the center), Patriots’ Park (because of the other memorials located there), or City Hall Park, it is a popular site for locals as well as tourists. Directly to Washington’s side stands a memorial to Francis Salvador, a Sephardic Jew who arrived in Charleston in 1773 at the age of 26. He had left his wife and four children in London and intended to send for them as soon as finances made it feasible, but the War of Independence changed his plans.

Almost immediately upon his arrival, he joined the cause for American independence and made his mark as the first Jew elected to public office in the 13 British colonies, serving in the South Carolina Provincial Congress.

Early in 1776, the British convinced their Cherokee Indian allies to attack the South Carolina frontier as a way of diverting the Americans from British operations on the sea coast. On July 1, 1776, the Indians began attacking frontier families in the district represented by Mr. Salvador. Mr. Salvador rode 28 miles to the nearest American militia to raise the alarm, earning himself the reputation as the Paul Revere of the South.

Having alerted the militia, he then took part in the military engagements that followed against local Tory supporters of the British and their Indian allies. On July 31, Mr. Salvador was shot and fell into some bushes, where he was discovered by Cherokees who scalped him. He died that night from his wounds at the age of 29, becoming the first Jew killed in the American Revolutionary War.

Mr. Salvador’s Jewish heritage is celebrated in Charleston as part of the patriot’s general biography. He was hardly the first Jew in Charleston.

Religious Freedom

In 1669, the charter of the Carolina Colony, drawn up by John Locke, granted liberty of conscience to all settlers, expressly including “Jews, heathens, and dissenters.” With this sort of welcome, Sephardic Jews, mostly from London, the Netherlands, the West Indies, and other British colonies, were among the early settlers in Charleston.

“In the Carolinas, you could own land and practice your religion. The influx of settlers attracted to the colony led Charleston to become the fourth largest city in America and the wealthiest city in the country,” said Ms. Kahn.

The earliest document of a Jew in Charleston dates to 1695, when at least one, presumed to be land-holder Simon Valentine, had become sufficiently fluent in the local native-American language to serve as an interpreter for the Europeans. Most historians assume that individual Jews had settled in the colony even earlier than that. By 1702, a substantial number of Jews participated in the local election.

Many of the early Jews seem to have been engaged in the practice of medicine or small businesses, although some were involved with the Barbados trade in rum and sugar.

In 1733, the London Sephardic community, encouraged by Joseph Salvador (Francis’s uncle, a prominent businessman, and the only Jewish director of the British East India Company), sent 42 Jews among other English settlers to Savannah in present-day Georgia. When Spain attacked Georgia in 1740, most of the Jewish families there, fearing that the Spanish Inquisition could be imposed on them, fled north to Charleston.

There, they thrived, becoming involved in business, trade, finance, and agriculture. Some became wealthy plantation owners. Many of the buildings which housed Jewish-owned stores still stand today and can be found throughout the city.

The First Shul

In any case, by 1749, there were a sufficient number of Jewish families to establish a Sephardic shul, Congregation Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim (KKBE). In 1786, another shul, named simply Congregation Beth Elohim, opened for Ashkenazi Jews.

In 1755, Joseph Salvador acquired 200,000 acres of land in the colony, which he distributed to other Sephardic Jews from London. This land, which became known as “Jews’ lands,” was a boon not only to the Jewish community, but to the Salvador family. The failure of the East India Company and the destruction of their properties in Portugal by the Lisbon earthquake of 1755 left them financially ruined. All they had left was the land in South Carolina.

In 1756, Moses Lindo, another Sephardic Jew from London, arrived and promptly became one of the largest traders in indigo in the region. Thanks to him, by 1776, this industry quintupled in South Carolina, and Mr. Lindo was appointed inspector-general of indigo.

Jews in the War of Independence

While Francis Salvador was the first Jew to die for the American cause during the Revolutionary War, he would not be the last. In 1779, a special unit of volunteer infantry was composed mostly of Charlestonian Jews, many of them bearing last names well known in the city’s history: David N. Cardozo (distinguished in the attempt to recapture Savannah), Jacob I. Cohen, Joseph Solomon (who was killed at the Battle of Beaufort, 1779), Jacob de la Motta, Jacob de Leon, Mark Lazarus, Mordecai Myers, and Mordecai Sheftall, who was a deputy commissary-general of issues for South Carolina and Georgia.

Benjamin Nones, a French Jew who served in Kazimierz Pulaski’s regiment, distinguished himself during the siege of Charleston and won praise from his commander for gallantry and daring.

In May 1780, a few prominent Jews in Charleston decided to throw their support to the British, especially when the city was occupied by British Lt-Gen Henry Clinton. The majority of Jews, however, remained patriots and left Charleston after the surrender. Most of them returned in 1783, and, one year later, the community founded a Hebrew Benevolent Society, which still exists.

Important Jewish Community

By 1800, South Carolina boasted some 2,000 Jews, most of them Sephardic, the largest Jewish population of any state in the US. Charleston, which had more Jews than any other town, city, or place in North America, became the unofficial capital of North American Jewry, a position it enjoyed until about 1830 when increasing numbers of Ashkenazic-German Jews emigrated to America, settling in New Orleans, Richmond, Savannah, Baltimore, and the northeast, particularly New York, Boston, and Philadelphia.

In the early 1800s, many Jews rose to hold high offices in South Carolina. Myer Moses, who had garnered praise for helping wounded American soldiers during the War for Independence, was elected to the state legislature in 1810 and later served as one of the first commissioners of education. Abraham Seixas was a magistrate, and Lyon Levy was state treasurer.

Jews were also intimately connected with the introduction of free-masonry to South Carolina. Emanuel de la Motta was a leading exponent of the movement, and Abraham Alexander, who served as an honorary reader at KKBE, was among those who introduced the Scottish rite to America. On the corner of Church and Broad Streets, there is a plaque honoring the founders of the Scottish Rite of Freemasonry. Four of the 12 founders were Jewish, and the plaque contains the Hebrew date as well as the civil one.

Jewish Charlestonians were also represented during the War of 1812. Jacob Valentine, probably a descendant of the first Jew mentioned in South Carolina’s annals, served in the Palmetto regiment. Charleston’s Dr. Jacob de la Motta served as a US Army surgeon during the War of 1812.

Break-Aways and the Reform Movement

Some observers have noted that the security enjoyed by Jews in Charleston is reflected in the internecine squabbles among various factions in the community. When Jews fear outbreaks of antisemitism or violence, there is not much energy left for synagogue battles. In Charleston, where KKBE was America’s largest Jewish congregation, there was plenty of time and energy for communal discord.

In 1824, a number of members of KKBE petitioned its trustees to shorten the davening and introduce English as the language for prayer. The petitions were rejected, prompting the petitioners to resign from the shul and organize their own “Reform Society of Israelites,” which is considered the beginning of the Reform movement in the US.

But the real split in the community arose following a fire in KKBE in 1840 which necessitated the rebuilding of the shul. Many members of KKBE, including the shul’s president, favored the Reform movement and wanted an organ introduced to the services. The Board of Trustees, however, consisted mostly of “Traditionalists,” who wanted the davening to remain unchanged and the organ to stay in the churches.

Although the shul’s constitution called for the Board of Trustees to vote on whether or not to adopt any new changes, the president refused to call for such a meeting. He suspected the Board would seek to admit new “traditionalist” members and, thus, take control of the congregation.

The Board subsequently met without having been called by the president, a move the Reformers challenged in civil court. In the resulting case, State v. Ancker, Judge A.P. Butler ruled that the Board had violated the synagogue’s constitution by meeting without the president’s approval and that the admission of the new members was invalid. The ruling allowed the Reformers to change religious ceremonies and observances.

The Traditionalists formed a new synagogue, Shearith Israel, but it existed only until 1866, when it reunited with KKBE, which is still a Reform congregation.

While the Traditionalists lost their Sephardic shul, in 1852, more recent Jewish immigrants to Charleston from Poland, Lithuania, Germany, and Prussia, established an Ashkenazic congregation they called Berith Shalome. The shul not only erected a building, but also a cemetery. After a few years, the spelling of the name changed to Brith Sholom.

Slavery

While most Jews were physicians, attorneys, peddlers, and shop owners, a few were ship owners who owed their fortunes to Charleston’s thriving port. Others were planters, and some owned sizable plantations.

According to Rhetta Mendelsohn, a member of the Charleston Jewish community and a certified city tour guide with a special interest in Jewish history, Jewish tourists are always surprised to discover that there were some Jewish slave owners.

“It was the labor force. It was the way of life. The Jews adapted to where they were and did what everybody else was doing here,” she said.

The modern city of Charleston does not hide its shameful historic involvement with slavery. The museums are filled with exhibitions demonstrating its horrors, and the Old Slave Mart on Chalmers Street, which was restored by the city and the South Carolina African-American Heritage Commission, houses a museum.

Jews in the Civil War

Jewish Charlestonians, like most of their white Gentile neighbors, supported the Southern cause, and fought and died with them during the Civil War.

Benjamin Mordecai is recognized as the first material contributor to the Confederacy, having donated $10,000 to South Carolina at the beginning of the war. His son was one of 182 Charlestonian Jewish soldiers to serve in the Rebel army. At least 25 of them died and are buried either in KKBE’s cemetery or the one operated by Brith Sholom.

The War Between the States began in Charleston in 1861 when Confederate artillery batteries opened fire on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. As a result, Charleston was besieged and shelled by Union forces during much of the war, leading many Charlestonians to flee the city.

Cong Brith Sholom was the only synagogue in Charleston to remain open during the war, providing kosher meat and matzah on Pesach.

Flourishing Orthodox Shul

Brith Sholom-Beth Israel Synagogue (BSBI)

The war left the South in general and Charleston in particular demoralized and in financial ruin. During Reconstruction, many Jews relocated to the Northern states, but a good number stayed, and they were joined by new immigrants, mostly from Eastern Europe and Germany.

In 1874, Brith Sholom erected a new building, and the dedication turned into a Jewish community-wide celebration. KKBE, by this time an established Reform congregation, honored the new Orthodox shul with an Aron Kodesh whose magnificent white Corinthian columns still grace the shul’s sanctuary.

By the end of the 19th century, Brith Sholom was recognized as the foremost Orthodox synagogue in the South.

But the growth of the shul was not without tensions. Families with long histories in Charleston were not always welcoming to the newcomers, and, in 1911, a sufficient number of new immigrants established their own Orthodox synagogue which they named Congregation Beth Israel. For the next 45 years, Charleston had two Orthodox shuls.

Consolidation

In 1947, some members of Brith Sholom suggested abandoning traditional Orthodoxy in favor of aligning with the new Conservative movement. The proposal was defeated by the majority of the members, but it led to the establishment of Charleston’s first Conservative synagogue, Congregation Emanu-El.

Shaken, the two Orthodox synagogues decided their differences paled in the face of this challenge, and they quickly joined forces, becoming one congregation, known to this day as Brith Sholom-Beth Israel, or BSBI.

Conveniently located near many of Charleston’s hotels, BSBI holds services every day of the week and on Shabbos. The beautiful and spacious shul, which has retained many of its and Beth Israel’s original decorative and architectural elements, can accommodate over 600 people.

Reservations to use BSBI’s mikveh should be made 24 hours in advance by calling the shul’s office at 843-577-6599.

The shul’s spiritual leader, Rabbi Moshe Davis, a musmach of Yeshiva University, is passionate about Jewish outreach. On Shabbat, he can frequently be found on the streets of downtown Charleston, often with his wife, Ariela, and any of their four children, wishing “Shabbat Shalom” to anyone they meet.

Eating Kosher

Eating kosher in Charleston can be tricky. In addition to kosher travelers’ usual routine of taking food along or ordering frozen meals to hotels which will heat them up, double-wrapped, on request, Rabbi Davis provides kosher certification to a number of establishments in town under the auspices of the Kosher Commission of Charleston. These include: King Street Cookies (370 King Street), offering cookies, bagels, and coffees; and Marty’s Place at 96 Wentworth Street, which is part of the dining services of the College of Charleston, offering a vegan and vegetarian restaurant.

While Publix and Earthfare grocery stores in Charleston are not under kosher supervision, they do carry a nice supply of products with reliable hechshers.

City Market

Perhaps one of the most enjoyable spots to visit in Charleston is its City Market, a double-sided, three-block long, open-air shed of vendors selling arts, crafts, food, souvenirs, knick-knacks, and even some antiques and Charlestonian relics. Sometimes called the Cultural Heart of Charleston, it has been operating since 1804. It is a wonderful place to find Southern-grown fresh fruits and vegetables and especially pecans.

In the market, don’t miss the many vendors working with sweetgrass to fashion baskets and other items. These hand-woven pieces represent one of the oldest handicrafts of African origin in the US. Made in Charleston from indigenous bulrush, a strong yet supple grass that thrives in the sandy soil of the coastal region, sweetgrass baskets begin with a knot around which coils of bundled grass are woven. While the materials are always the same, the design varies from artist to artist. One of the craftsmen fashioned an interwoven basket that would make a delightful seder plate.

Located at 188 Meeting Street, the market can be reached at 843-937-0920. The Day Market is open daily from 9:30am to 6pm. The Charleston City Night Market is open from 6:30-10:30pm on Sundays, from March through December, and on the third Thursday of every month. It is open Motzei Shabbat until 10:30pm, too.

Hyman’s

At 215 Meeting Street, in the heart of historic Charleston, sits Hyman’s Seafood and Aaron’s Deli, a distinctly non-kosher restaurant—with a delightful, if surprising, kosher twist.

On the same site in 1890, the current owners’ Jewish immigrant great-great-grandfather, Wolf Maier Karesh, started his Southern Wholesale dry goods business, which became the first distributor of Union & Hanes underwear in the Southeast.

In 1924, Mr. Karesh’s son-in-law, Herman Hyman, took over the business and changed the name to Hyman’s Wholesale Company. He passed the business down to a third generation, Wolf Maier Hyman, who continued selling dry goods until 1986. His sons, Eli and Aaron Hyman, turned the property into Hyman’s Seafood and Aaron’s Deli. Aaron is now retired, and his son-in-law, Brad Gena, is Eli’s operating partner.

Kosher Dining Donated to Chabad

Hyman’s Seafood’s Glatt Kosher Menu

Perhaps nothing is quite as amazing as Hyman’s menu. Standing boldly among Charleston’s typically treif lump crab cakes, gator sausage, shrimp anyway-you-like-it, and fried or grilled pork chops, is the restaurant’s Glatt Kosher Dinner menu, certified by Rabbi Yossi Refson of Chabad of Charleston and the Low Country.

The menu proudly announces that “100 percent of the proceeds” of these glatt kosher meals, which come hot, completely sealed, and double-wrapped, is donated directly to Chabad. Diners are then invited to make their own contributions, too.

At Hyman’s, kosher diners can order matza ball soup followed by entrees of salmon, chicken, meatballs, stuffed cabbage, or beef brisket. Non-dairy desserts are available as are bottles of kosher white or red wine. Small and large loaves of freshly made challahs are on the menu, too.

These kosher meals are available all days of the week, and can be pre-paid for Shabbos.

Often, Hyman’s diners can meet with members of the Hyman family, but not on Friday nights, when they are usually home enjoying their own Shabbos meals.

Perhaps the most surprising moment of a visit to Hyman’s comes when diners look at the cards placed on each table for their reading pleasure while waiting to be served. Right in the middle of cards offering snippets of typical folk wisdom are teachings of Rabbi Yisroel Salanter.

Who to Call

Those planning a trip to Charleston, would be well advised to contact Ms. Kahn of Chai Y’All Tours at 843-556-0664.

With or without a guide, some sites of Jewish interest that should not be missed include:

KKBE, 90 Hasell Street, which runs docent-led tours of its building and museum Monday through Friday at 10:15am, 11:15am, 1pm, and 2pm, and on Sundays at 1pm, 2pm, and 3pm. It also conducts tours of the Coming Street Jewish Cemetery, which was established in 1762. The number is 843-723-1090.

Brith Sholom Beth Israel (BSBI) Synagogue, Rabbi Moshe Davis, 182 Rutledge Ave, 843-577-6599

Charleston’s Holocaust Memorial on the edge of the Francis Marion Park

The Jewish Heritage Collection at the College of Charleston on Calhoun Street, 843-953-8028

Free lectures, meals, and programs at the Yaschik/Arnold Jewish Studies Program, 96 Wentworth Street, 843-953-7624

Chabad of Charleston and the Low Country, Rabbi Yossi Refson, 843-884-2323

And keep checking the website SpoletoUSA.org. The 2017 season, which will run from May 26-June 11 (Shavuot is May 31 and June 1), will be announced sometime in January.

S.L.R.